| Original Works by Joe Ryan @ AmericanCivilWar.com What Caused the Civil War |

The Dred Scott Decision

|

Kindle Available Raising Freedom's Child: Black Children and Visions of the Future After Slavery Previously untapped documents and period photographs casts a dazzling, fresh light on the way that abolitionists, educators, missionaries, planters, politicians, and free children of color envisioned the status of African Americans after emancipation |

One of the most important cases ever tried in the United States was heard in St. Louis' Old Courthouse. The two trials of Dred Scott in 1847 and 1850 were the beginning of a complicated series of events which concluded with a U.S. Supreme Court decision in 1857, and hastened the start of the Civil War.

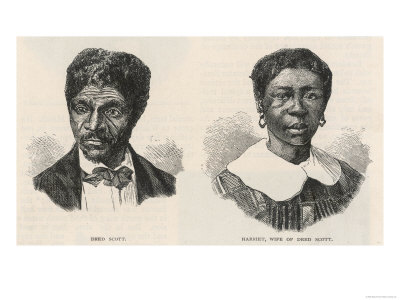

On April 6th, 1846, Dred Scott and his wife Harriet filed suit against Irene Emerson for their freedom. For almost nine years, Scott had lived in free territories, yet made no attempt to end his servitude. It is not known for sure why he chose this particular time for the suit, although historians have considered three possibilities: He may have been dissatisfied with being hired out; Mrs. Emerson might have been planning to sell him; or he may have offered to buy his own freedom and been refused. It is known that the suit was not brought for political reasons. It is thought that friends in St. Louis who opposed slavery had encouraged Scott to sue for his freedom on the grounds that he had once lived in a free territory. In the past, Missouri courts supported the doctrine of "once free, always free." Dred Scott could not read or write and had no money. He needed help with his suit. John Anderson, the Scott's minister, may have been influential in their decision to sue, and the Blow family, Dred's original owners, backed him financially. The support of such friends helped the Scotts through nearly eleven years of complex and often disappointing litigation. It is difficult to understand today, but under the law in 1846 whether or not the Scotts were entitled to their freedom was not as important as the consideration of property rights. If slaves were indeed valuable property, like a car or an expensive home today, could they be taken away from their owners because of where the owner had taken them? In other words, if you drove your car from Missouri to Illinois, and the State of Illinois said that it was illegal to own a car in Illinois, could the authorities take the car away from you when you returned to Missouri? These were the questions being discussed in the Dred Scott case, with one major difference: your car is not human, and cannot sue you. Although few whites considered the human factor in Dred Scott's slave suit, today we acknowledge that it is wrong to hold people against their will and force them to work as people did in the days of slavery. |

Dred and Harriet Scott 24 in. x 18 in. Buy at AllPosters.com Framed Mounted |

Kindle Available The Dred Scott Case: Its Significance in American Law and Politics Winner of the Pulitzer Prize in 1979. Chief Justice Roger B. Taney delivered the Supreme Court's decision against Dred Scott |

The Dred Scott case was first brought to trial in 1847 in the first floor, west wing courtroom of St. Louis' Courthouse. The Scotts lost the first trial because hearsay evidence was presented, but they were granted the right by the judge to a second trial. In the second trial, held in the same courtroom in 1850, a jury heard the evidence and decided that Dred Scott and his family should be free. Slaves were valuable property, and Mrs. Emerson did not want to lose the Scotts, Dred Scott was not ready to give up in his fight for freedom for himself and his family, however. With the help of a new team of lawyers who hated slavery, Dred Scott filed suit in St. Louis Federal Court in 1854 against John F.A. Sanford, Mrs. Emerson's brother and executor of the Emerson estate. Since Sanford resided in New York, the case was taken to the Federal courts due to diversity of residence. The suit was heard not in the Old Courthouse but in the Papin Building, near the area where the north leg of the Gateway Arch stands today. The case was decided in favor of Sanford, but Dred Scott appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. On March 6th, 1857, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney delivered the majority opinion of the U.S. Supreme Court in the Dred Scott case. Seven of the nine justices agreed that Dred Scott should remain a slave, but Taney did not stop there. He also ruled that as a slave, Dred Scott was not a citizen of the United States, and therefore had no right to bring suit Ironically, Irene Emerson was remarried in 1850 to Calvin C. Chaffee, a northern congressman opposed to slavery. After the Supreme Court decision, Mrs. Chaffee turned Dred and Harriet Scott and their two daughters over to Dred's old friends, the Blows, who gave the Scotts their freedom in May 1857. On September 17, 1858, Dred Scott died of tuberculosis and was buried in St. Louis. His grave was moved in the 1860s to Calvary Cemetery in northern St. Louis, and marked due to the efforts of the Rev. Edward Dowling in 1957. Dred Scott did not live to see the fratricidal war touched off at Fort Sumter in 1861, but did live to gain his freedom. The ultimate result of the war, the end of slavery throughout the United States, was not something Dred Scott could have foreseen in 1846, when he decided to sue for his freedom in St. Louis' Old Courthouse. |

|

Kindle Available The Missouri Compromise and Its Aftermath: Slavery and the Meaning of America Go behind the scenes of the crucial Missouri Compromise, the most important sectional crisis before the Civil War, the high-level deal-making, diplomacy, and deception that defused the crisis Young Reader Title  Eye Witness Civil War Eyewitness Civil War includes everything from the issues that divided the country, to the battles that shaped the conflict, to the birth of the reunited states. Rich, full-color photographs of rare documents, powerful weapons, and priceless artifacts plus stunning images of legendary commanders, unsung heroes, and memorable heroines More Young Reader Books |

The Waterman's Song: Slavery and Freedom in Maritime North Carolina |

Colored Civil War Troops African American Timeline Underground Railroad Kids Zone Underground Railroad Frederick Douglass Women in the Civil War Civil War Documents Civil War Exhibits Civil War Timeline |

Civil War Model 1851 Naval Pistol Engraved Silver Tone / Gold Tone Finish and Wooden Grips - Replica of Revolver Used by Both USA / Union and CSA / Confederate Forces |

Early American Abolitionists: A Collection of Anti-slavery Writings, 1760-1820 This compilation reprints fifteen anti-slavery texts that, almost without exception, have been out of print for nearly two centuries. The pamphlets, poems, letters, and other documents by anti-slavery writers-men and women, black and white-demonstrate that abolitionists were active in the early years of the American republic. The book's texts are reprinted with short introductions written by 12 Gilder Lehrman history scholars. |

Bitter Fruits Of Bondage: The Demise Of Slavery And The Collapse Of The Confederacy, 1861-1865 The process of social change initiated during the birth of Confederate nationalism undermined the social and cultural foundations of the southern way of life built on slavery, igniting class conflict that ultimately sapped white southerners of the will to go on. |

Prelude to Civil War: The Nullification Controversy in South Carolina From 1816 to 1836 planters of the Palmetto State tumbled from a contented and prosperous life to a world rife with economic distress, guilt over slavery, and apprehension of slave rebellion. Compelling details ofhow this reversal of fortune led the political leaders down the path to states rights doctrines |

A House Divided: The Antebellum Slavery Debates in America, 1776-1865 An excellent overview of the antebellum slavery debate and its key issues and participants. The most important abolitionist and proslavery documents written in the United States between the American Revolution and the Civil War |

To 'Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women's Lives and Labors after the Civil War Thousands of former slaves flocked to southern cities in search of work, they found the demands placed on them as wage-earners disturbingly similar to those they had faced as slaves: seven-day workweeks, endless labor, and poor treatment |

Kindle Available Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America The evolution of black society from the first arrivals in the early seventeenth century through the Revolution |

Kindle Available Political Culture and Secession in Mississippi: Masculinity, Honor, and the Antiparty Tradition, 1830-1860 A rich new perspective on the events leading up to the Civil War and will prove an invaluable tool for understanding the central crisis in American politics. |

Kindle Available Nothing but Freedom Emancipation and Its Legacy Insights into the relatively neglected debates over fencing laws and hunting and fishing rights in the postemancipation South, and into the solidarity of the low-country black community |

Freedom Train: The Story of Harriet Tubman Harriet escaped North, by the secret route called the Underground Railroad. Harriet didn't forget her people. Again and again she risked her life to lead them on the same secret, dangerous journey. |

Kindle Available The Glory Cloak: A Novel of Louisa May Alcott and Clara Barton From childhood, Susan Gray and her cousin Louisa May Alcott have shared a safe, insular world of outdoor adventures and grand amateur theater -- a world that begins to evaporate with the outbreak of the Civil War. Frustrated with sewing uniforms and wrapping bandages, the two women journey to Washington, D.C.'s Union Hospital to volunteer as nurses. |

Clara Barton Founder of the American Red Cross Young Clara Barton is shy and lonely in her early days at boarding school. She is snubbed by the other girls because she doesn't know how to talk to them. But when she gets an opportunity to assist the local doctor, her shyness disappears, and Clara begins to discover her true calling as a nurse. |

Grace's Letter to Lincoln Many important details of the time period help to make the reader understand what life was like then. It also includes photos of the actual letters written between Grace and Mr. Lincoln |

Allen Jay and the Underground Railroad Allen Jay and the Underground Railroad is the retelling of a man's recollections of his first experience helping an escaped slave. The book brings the underground railroad down to the level primary students can comprehend. This book makes for wonderful discussions regarding overcoming one's fears, going against the norm and doing what you believe to be morally correct. |

Numbering The Bones The Civil War is at an end, but for thirteen-year-old Eulinda, it is no time to rejoice. Her younger brother Zeke was sold away, her older brother Neddy joined the Northern war effort,. With the help of Clara Barton, the eventual founder of the Red Cross, Eulinda must find a way to let go of the skeletons from her past. |

Night Boat To Freedom Night Boat to Freedom is a wonderful story about the Underground Railroad, as told from the point of view of two "ordinary" people who made it possible. Beyond that, it is a story about dignity and courage, and a devotion to the ideal of freedom. |

Voice of Freedom A Story About Frederick Douglass Interesting for both children and adults, this book does much to evoke the strong-minded, highly-principled person who inspired so many others |

Wargame Construction Age of Rifles 1846 - 1905 Game lets you design and play turn-based strategic battles. You can create scenarios betwen years 1846 and 1905. You have complete control over all the units, and can customize their firepower, movement points, strength, aggressiveness, etc. Supports 1 or 2 players |

History Channel Civil War A Nation Divided Rally the troops and organize a counterattack -- Your strategic decision and talent as a commander will decide if the Union is preserved or if Dixie wins its independence |

Sid Meier's Civil War Collection Take command of either Confederate or Union troops and command them to attack from the trees, rally around the general, or do any number of other realistic military actions. The AI reacts to your commands as if it was a real Civil War general, and offers infinite replayability. The random-scenario generator provides endless variations on the battles |

Campaign Gettysburg: Civil War Battles Campaign Gettysburg is simply the best of all the HPS Civil War games. While all of those are very good in their own right they simply do not compete with the level of detail presented here. Hundreds of scenarios and multiple OOBs are only the start, the best thing is the campaign game |

Source:

National Park Service

Federal Citizen

|

Books Civil War Womens Subjects Young Readers Military History DVDs Confederate Store Civil War Games Music CDs Reenactors |