Foreword

Commerce raiding has always been a recognized and accepted method of sea

warfare. It is probable that no individual naval commander nor any single ship

in our long history has recorded a more spectacular success in that field than

Captain Raphael Semmes of the Confederate Navy and his C. S. S. Alabama.

Captain Semmes very fortunately let his pen flow fluently when he recorded

these many eventful successes. They are noted in the Civil War Naval

Chronology published by the Naval History Division (later Naval Historical

Center) of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations.

This pamphlet has been prepared with the belief that it will provide an

interesting and sometimes even an amusing, as well as a historical record, of

the celebrated raider and her distinguished captain Raphael Semmes.

official photographs courtesy of Naval History Division

office of Chief

of Naval Operations

--i--

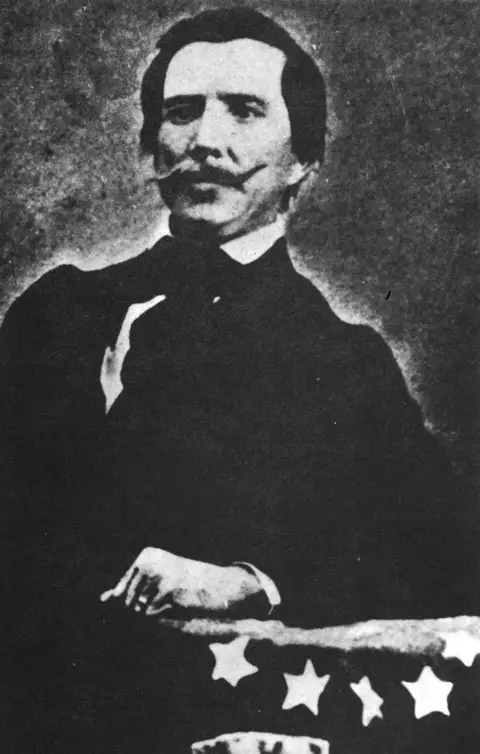

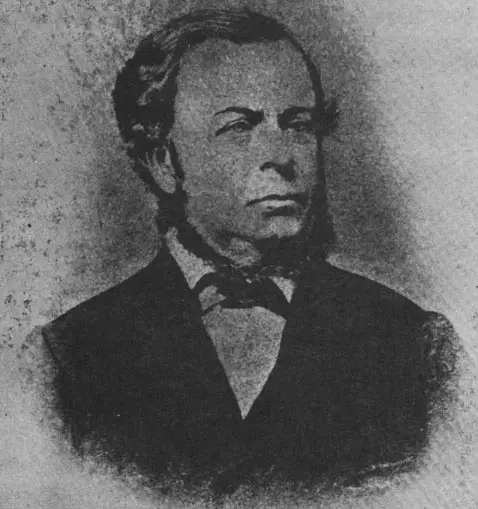

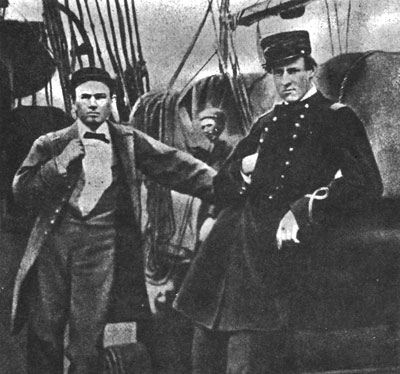

Captain

Raphael Semmes, CSN

--ii--

Captain Raphael Semmes and the C.S.S. Alabama

The Ship

In his inaugural address as President of the Provisional Government of the

Confederate States on 18 February 1861, Jefferson Davis said, "I ... suggest

that for the protection of our harbors and commerce on the high seas a Navy

adapted to those objects will be required ... " Three days later he appointed

Stephen R. Mallory of Florida as Secretary of the Confederate Navy. On 26 April,

Mallory reported: "I propose to adopt a class of vessels hitherto unknown to

naval services. The perfection of a warship would doubtless be a combination of

the greatest known ocean speed with the greatest known floating battery and

power of resistance ... agents of the department have thus far purchased but two

[steam vessels], which combine the requisite qualities. These, the Sumter and

McRae, are

being fitted as cruisers ... Vessels of this character and capacity cannot be

found in this country, and must be constructed or purchased abroad."

A Secret Act of the Confederate Congress signed on 10 May 1861 by President

Davis authorized "the Navy Department to send an agent abroad to purchase six

steam propellers, in addition to those heretofore authorized, together with

rifled cannon, small arms, and other ordnance stores and munitions of war," and

appropriated a million dollars for the purpose. In furtherance of that

intention, on 9 May 1861, Mallory had ordered Commander James Dunwoody Bulloch,

CSN, to England to purchase ships, guns and ammunition. Bulloch had been a

former U.S. Naval officer and was reputed to be one of the most capable shipping

experts in the United States. In his instructions, the Secretary said: " ...

provide as one of the conditions of payment for the delivery of the vessels

under the British flag at one of our Southern ports, and, secondly, that the

bonds of the Confederacy be taken in whole or in part payment. The class of

vessel desired for immediate use is that which offers the greatest chances of

success against the enemy's commerce ... as side-wheel steamers can not be made

general cruisers, and as from the enemy's force before our forts, our ships must

be enabled to keep the sea, and to make extended cruises, propellers fast under

both steam and canvas suggest themselves to us with special favor. Large ships

are unnecessary for this service; our policy demands that they shall be no

larger than may be sufficient to combine the requisite speed and power, a

battery of one or two heavy pivot guns and two or more broadside guns, being

sufficient against commerce. By getting small ships we can afford a greater

number, an important consideration. The character of the coasts and harbors

indicate attention to the draft of water of our vessels. Speed in a propeller

and the protection of her machinery can not be obtained upon a very light draft,

but they should draw as little water as may be compatible with their efficiency

otherwise."

--1--

Stephen

R. Mallory,

Secretary of the Navy, Confederate States, 1861-1865

Bulloch arrived in Liverpool on 3 June 1861 and, on 1 August of that year,

made a contract with Laird Brothers of Birkenhead, near Liverpool, to build the

Alabama. This happened to be the 290th ship to be built by that yard. The

ship was known by the designation hull "290" during building. It was launched

under the name of Enrica.

The ship was 220 feet long with a 32 foot beam and a 15 foot draft when fully

coaled and provisioned. Her wooden hull was fastened with copper and her bottom

was copper sheathed to reduce fouling. She was barkentine-rigged. Her long lower

masts enabled her to carry large fore-and-aft sails as jibs and topsails. Her

masts were of yellow pine and her rigging was of the best Swedish wire. She had

an auxiliary steam engine of 300 horsepower, bunker capacity for 285 tons of

coal, and a distilling plant which provided the crew with an ample supply of

fresh water. Her propeller could be detached from the shaft in about 15 minutes

and hoisted into a well clear of the water. Her speed was about 10 knots but,

when under both sail and steam, she could do about 13. The estimated cost of the

completed Alabama was 250,000 dollars, paid for in part or full with

Confederate bonds.

--2--

Her armament consisted of eight guns, six-32 pounders in broadside, two pivot

guns amidships, one on the forecastle, the other abaft the mainmast. The

forecastle gun was a 100 pounder rifled Blakeley, the after gun was a smooth

bore eight pounder. She had a crew of about 120 men and 24 officers, the

Captain, 4 Lieutenants, a Surgeon, Paymaster, Master Marine Officer, 4

Engineers, 2 Midshipmen, 4 Master Mates, a Captain's Clerk, Boatswain, Gunner,

Sailmaker, and Carpenter. The crew was made up of men from the #290 who had

taken her to sea, those of the Bahama who

voluntarily signed up to serve with Semmes and, from his own statement," ...

about sixty persons who had been picked promiscuously, about the streets of

Liverpool ... " Many of the officers had served with Semmes in the

Sumter, now out of commission at Gibraltar.

Great Britain, as a neutral nation, came under much pressure from the United

States Government to stop the building of ironclads and other men-of-war for the

Confederacy. On 13 May 1861, Queen Victoria had issued a "Proclamation of

Neutrality" which prohibited the sale of ships of war. Vessels could, however,

enter United Kingdom waters but could not alter or improve their equipment while

there. In the case of this ship, the pressure was so great that court action

almost kept her from sailing on her sea trials. Mr. Charles Francis Adams,

American Minister to London, delivered a formal note to the Foreign office on 23

June 1862, submitted as a statement by the United States Consul at Liverpool

detailing the suspicious circumstances connected with the vessels being built by

the Laird firm. The British authorities, however, found the evidence not

sufficient to establish that a violation of the act was contemplated. Repeated

efforts to delay or prevent the delivery of the ship were unsuccessful. On 29

July 1862, without armament, she left Liverpool supposedly on a trial run. To

allay any suspicions in that respect, a party of ladies and custom officials

were taken on board for the trip. A short distance at sea, however, the

passengers were transferred to a tug and returned to port while the ship itself,

under the command of Captain Matthew S. Butcher, proceeded down the coast about

50 miles to Anglesey. The ship spent two days there preparing for sea; and, on

31 July, headed into the Irish Sea where Bulloch and the pilot were landed at

the Giant Causeway on the north coast of Ireland. The ship then sailed to her

prearranged destination. Bulloch had already purchased the guns, gun mounts,

ammunition, ordnance stores, clothing, provisions and coal to fit the ship out

as a raider. They had been loaded into the bark Agrippina

and she sailed to rendezvous with the #290 at the eastern end of the island of

Terceira in the Azores. The transfer of equipment began immediately upon her

arrival there and actually before the raider's captain had arrived.

--3--

The Captain

The naval career of the only officer to command this famous raider began just

about 36 years earlier. Raphael Semmes was born in Maryland in 1809, brought up

in Georgetown, and appointed a midshipman in 1826, before the Naval Academy was

established. He received his training at sea and became a Passed Midshipman in

1832 standing first in his class. After 6 years at sea, he was assigned to the

naval base at Norfolk to maintain the fleet chronometers. Ambitious and

studious, Semmes studied law while on that duty and was admitted to the bar.

After 3 years at Norfolk, he was assigned to the U.S.S. Constellation.

He became a Lieutenant in 1837 and married Anne Elizabeth Spencer. In 1841 he

was assigned to the Pensacola Navy Yard and while there became a citizen of

Alabama. Lieutenant Semmes' first command afloat was the steamship Poinsett.

Later in 1846 he commanded the ill-fated brig Somers which

capsized in a squall and sank with the loss of many of her crew. A court of

inquiry acquitted Semmes and he was sent to Mexico City during the Mexican War

to work with the Army as a member of the Staff of General W.J. Worth.

After the Mexican War, Lieutenant Semmes was in "an awaiting orders" status

and spent most of his time in Mobile where he practiced law. In 1855 he was

promoted to Commander and assigned to duty with the Lighthouse Board in

Washington. He remained there until he resigned his commission in the U.S. Navy

on 15 February 1861, offered his services to the South, and went to Montgomery,

Alabama, capitol of the Confederacy.

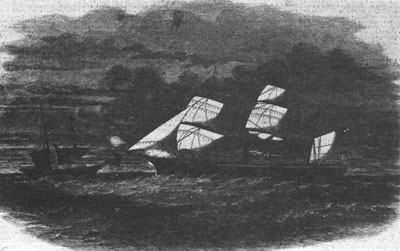

The

Pirate Sumter firing at the Brig Joseph Parks of Boston --

Sketched by one of the crew of the Sumter

--4--

Semmes' first assignment in the Confederate Navy sent him to the northern

states to purchase ships and munitions and to recruit skilled mechanics. Later,

he was given command of the small ship Habana, which was renamed C.S.S.

Sumter, the first Confederate raider. Semmes began his adventurous career

on 30 June 1861 when he ran the Sumter through the Federal blockade at

the mouth of the Mississippi River, eluding the U.S.S. Brooklyn. As

he broke the flag on his ship and took the sea, he wrote, the crew "gave three

hearty cheers for the flag of the Confederate States, thus ... thrown to the

breeze on the high seas by a ship of war." He confined the operations of the

Sumter to the Caribbean until late November of 1861 and then set sail for

European waters. Continuing his commerce destruction enroute, he arrived in the

Straits of Gibraltar in January 1862. His operations in that area were not too

successful; nevertheless, U.S.S. Kearsarge

was ordered to Cadiz, Spain in an effort to track him down. In a letter of 6

March 1862 to Mr. J.M. Mason, the Confederate Commissioner in London, he wrote,

" ... it is quite manifest that there is a combination of all the neutral

nations against us in this war and that in consequence we shall be able to

accomplish little or nothing outside of our own waters. The fact is, we have got

to fight this war out by ourselves, unaided, and that, too, in our own terms ...

" Finally, on 7 April 1862, he was ordered to lay up his ship. Semmes left

Gibraltar enroute home but when he reached Nassau he was ordered to command the

Alabama. Together with some of his officers from the Sumter, he

reached Liverpool on 8 August 1862.

On 13 August, he and Commander Bulloch sailed on the chartered steamer

Bahama for the Azores where he arrived on 20 August. He records his

arrival there and his first impression of his new command in these words, "At

half-past eleven A.M., we steamed into the harbor, and let go our anchor. I had

surveyed my new ship ... with no little interest, as she was to be not only my

home, but my bride, as it were, for the next few years, and I was quite

satisfied with her external appearance. She was, indeed, a beautiful thing to

look upon."

The Commissioning

The transfer of the equipment from the Agrippina to the #290 was

completed in the short period of four days. Semmes said: "I had arrived on

Wednesday, and on Saturday night, we had, by dint of great labor and

perseverance, drawn order out of chaos. The Alabama's battery was on

board, and in place, her stores had all been unpacked, and distributed to the

different departments, and her coal-bunkers were again full." The ship put to

sea on Sunday, 24 August 1862. On that date, Semmes was promoted to Captain, the

ship was commissioned off Terceira, and Semmes assumed

--5--

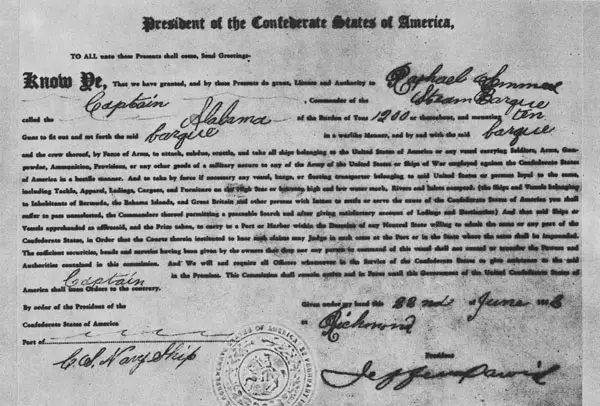

command. There is no better way to describe this ceremony than to quote the

words of her distinguished skipper: "The ship having been properly prepared, we

steamed out, on this bright Sunday morning, under a cloudless sky, with a gently

breeze from the southeast, scarcely ruffling the surface of the placid sea, and

under the shadow of the smiling and picturesque island of Terceira, which nature

seemed to have decked specially for the occasion, so charming did it appear, in

its checkered dress of a lighter and darker green, composed of cornfields and

orange-groves, the flag of the new-born Confederate States was unfurled, for the

first time, from the peak of the Alabama. The Bahama accompanied

us. The ceremony was short but impressive. The officers were all in full

uniform, and the crew neatly dressed, and I caused 'all hands' to be summoned

aft on the quarter-deck, and mounting a gun-carriage, I read the commission of

Mr. Jefferson Davis, appointing me a captain in the Confederate States Navy, and

the order of Mr. Stephen R. Mallory, the Secretary of the Navy, directing me to

assume command of the Alabama. Following my example, the officers and

crew had all uncovered their heads, in deference to the sovereign authority, as

is customary on such occasions; and as they stood in respectful silence and

listened with rapt attention to the reading, and to the short explanation of my

object and purposes, in putting the ship in commission which followed, I was

deeply impressed with the spectacle. Virginia, the grand old mother of many of

the States, who afterward died so nobly; South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, and

Louisiana were all represented in the persons of my officers, and I had some of

as fine specimens of the daring and adventurous seaman, as any ship of war could

boast. While the reading was going on, two small balls might have been seen

ascending slowly, one to the peak, and the other to the main-royal masthead.

These were the ensign and pennant of the future man-of-war. These balls were so

arranged, that by a sudden jerk of the halliards by which they had been sent

aloft, the flag and pennant would unfurl themselves to the breeze. A curious

observer would also have seen a quartermaster standing by the English colors,

which we were still wearing, in readiness to strike them, a band of music on the

quarterdeck, and a gunner (lock-string in hand) standing by the weather-bow gun.

All these men had their eyes upon the reader; and when he had concluded, at a

wave of his hand the gun was fired, the change of flags took place, and the air

was rent by a deafening cheer from officers and men; the band, at the same time,

playing 'Dixie,' -- that soul-stirring national anthem of the new-born

government. The Bahama also fired a gun and cheered the new flag. Thus,

amid this peaceful scene of beauty, with all nature smiling upon the ceremony,

was the Alabama christened; the name '290' disappearing with the English

flag. This had all been done upon the high seas .... "

--6--

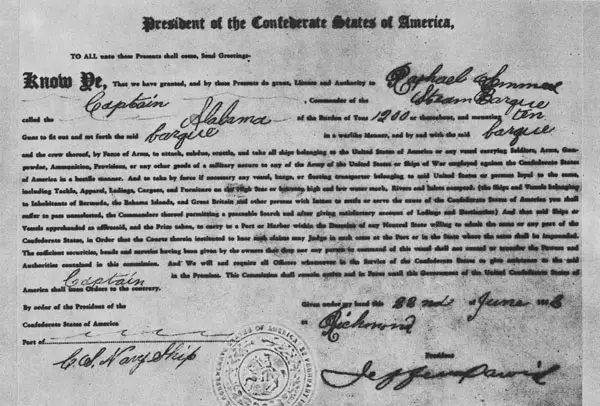

Captain

Semmes' commission to command Alabama

--7--

Operations in the Atlantic

Semmes wasted little time after commissioning his new raider to start his

operations. A fleet of American whaling ships was in the waters around the

Azores, and their destruction became his immediate objective. Within one month

he had captured and burned nine ships of this fleet. After his last victim, he

wrote: "The whaling season at the Azores being at an end ... I resolved to

change my cruising-ground, and stretch over to the Banks of New Foundland ...."

His first prize in these new waters, which he captured and burned on 3 October

1862, was the American ship Brilliant from New York to Liverpool. He

later commented that "... her destruction must have disappointed a good many

holders of bills of exchange drawn against her cargo ... for the ship alone and

the freight-moneys which they lost by her destruction [came] to the amount of

$93,000. The cargo was probably even more valuable than the ship." During

October of 1862, he captured nine more American vessels in the area. One, the

American ship Manchester, was also from New York to Liverpool. Semmes

notes that: "The Manchester brought us a batch of late New York papers

... I learned from them where all the enemy's gun boats were, and what they were

doing. . .. Perhaps this was the only war in which the newspapers ever

explained, before-hand, all the movements of armies and fleets, to the enemy."

Semmes burned most of his captured ships; two, however, the packet

Tonowanda and the brigantine Baron de Castine were released on

bond. Of the latter, Semmes wrote, on 29 October 1862: "The vessel being old and

of little value, I released her on ransom bond and converted her into a cartel,

sending some forty-five prisoners on board of her---the crews of the three last

ships burned."

That the operations of the Alabama even in these few months were of

concern to the Union is indicated by a letter written by the Assistant Secretary

of the Navy Fox to Edward G. Flynn, on 30 October 1862, regarding that man's

expressed desire to attempt capture or destruction of the Alabama. Fox

wrote: "The [Navy] Department has published that it will give $500,000 for the

capture and delivery to it of that vessel, or $300,000 if she is destroyed; the

latter however is to be contingent upon the approval of Congress." Secretary Fox

also wrote a letter to Rear Admiral Farragut about the same time in which he

said, "The raid of '290' [Alabama] has forced us to send out a dozen

vessels in pursuit."

Neither the offer of rewards for capture or destruction, nor the pursuing

vessels, were effective against the daring Semmes. By November he had shifted

his cruising ground to the southward where during that month he captured and

burned three vessels off Bermuda and the Leeward Islands. He had arrived off

Martinique, on 18 November, where he found the port blockaded by U.S.S. San

Jacinto (of the Trent Affair) which he evaded and escaped in foul

weather on the 19th. Still in West Indian waters, he captured

--8--

and released on bond ship Union, on 5 December 1862; and, on the 7th,

he captured California steamer Ariel off the coast of Cuba, with 700

passengers including 150 Marines and Commander Louis C. Sartori, USN.

In his first four months of operations, Semmes had captured 25 ships. He

burned 22 of them and released three on bond.

In January 1863, Semmes took his raider into the Gulf of Mexico where he

believed he would find many Union transports off Galveston. On 11 January, in a

close night engagement thirty miles off that port, he met and sank the U.S.S.

Hatteras

commanded by Lieutenant Commander Homer C. Blake. Semmes reported this

engagement in these words: "My men handled their pieces with great spirit and

commendable coolness, and the action was sharp and exciting while it lasted;

which, however, was not very long, for in just thirteen minutes after firing the

first gun, the enemy hoisted a light, and fired an off-gun, as a signal that he

had been beaten. We at once withheld our fire, and such a cheer went up from the

brazen throats of my fellows, as must have astonished even a Texan, if he had

heard it." Whereas the Hatteras was fatally damaged, Semmes writes of the

Alabama: " ... that there was not a shot-hole which it was necessary to

plug, to enable us to continue our cruise; nor was there a rope to be spliced."

Hatteras went down in 9-1/2 fathoms, Alabama saving all hands.

Other Union ships in the Galveston area put to sea in vain chase of the raider

and Semmes observed: "There was now as hurried a saddling of steeds for the

pursuit as there had been in the chase of the young Lochinvar, and with as

little effect, for by the time the steeds were given the spur, the

Alabama was distant a hundred miles or more."

After the engagement, Semmes sailed for Jamaica where, on 20 January 1863,he

put the Hatteras crew ashore at Port Royal. On 26 January, off Haiti, he

captured and burned ship Golden Rule. Semmes wrote in his log: "This

vessel had on board masts, spars, and a complete set of rigging for the U.S.

brig Bainbridge,

lately obliged to cut away her masts in a gale at Aspinwall [Panama]." He later

added: "I had tied up for a while longer, one of the enemy's gun-brigs, for want

of an outfit. It must have been some months before the Bainbridge put to

sea." The next day brig Chastelaine, enroute to Cienfuegos, Cuba, for a

cargo of sugar and rum for Boston met the same fate. Life on board

Alabama itself was not uneventful for, on 2 February 1863, a fire broke

out. Although it was quickly extinguished, it prompted Semmes to note: "The

fire-bell in the night is sufficiently alarming to the landsman, but the cry of

fire at sea imports a matter of life and death--especially in a ship of war,

whose boats are always insufficient to carry off her crew, and whose magazine

and shellrooms are filled with powder and the loaded missiles of death."

--9--

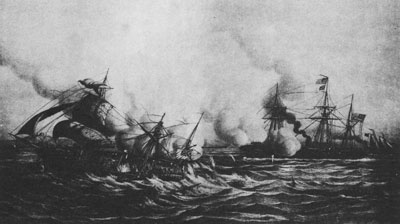

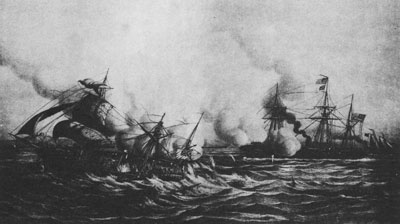

Sinking

of the Hatteras by Alabama (290)

The following day schooner Palmetto, from New York for San Juan with a

cargo of provisions, was captured and burned. Semmes took this occasion to extol

the characteristics of his own ship in these words: "It was beautiful to see how

the Alabama performed her task, working up into the wind's eye, and

overhauling her enemy, with the ease of a trained courser coming up with a

saddle-nag." Almost three weeks passed before Semmes fell in with other victims,

but on 21 February a particularly valuable cargo was destroyed when Semmes

captured and burned ship Golden Eagle in mid-Atlantic, of which he wrote:

"I had overhauled her near the termination of a long voyage. She had sailed from

San Francisco, in ballast, for Howland's Island, in the Pacific; a guano island

of which some adventurous Yankees had taken possession. There she had taken in a

cargo of guano, for Cork ... This ship [Golden Eagle] had buffeted the

gales of the frozen latitudes of Cape Horn, threaded her pathway among its

ice-bergs, been parched with the heats of the tropic, and drenched with the

rains of the equator, to fall into the hands of her enemy, only a few hundred

miles from her port. But such is the fortune of war. It seemed a pity, too, to

destroy so large a cargo of a fertilizer, that would also have made fields

stagger under a wealth of grain. But those fields would have been the fields of

the enemy; or if it did not fertilize his fields, its sale would pour a stream

of gold into his coffers; and it was my business upon the high seas, to cut off,

or dry up this stream of gold .... how fond the Yankees had become of the

qualifying adjective, 'golden,'

--10--

as a prefix to the names of their ships. I had burned the Golden

Rocket, the Golden Rule, and the Golden Eagle." Bark Olive

Jane was destroyed the same day. Six days later, in the same area, ship

Washington was captured and released on bond. Semmes wrote: "She was

obstinate, and compelled me to wet the people on her poop, by the spray of a

shot, before she would acknowledge that she was beaten."

March 1863 started off well for the raider. On the 2nd, he captured and

burned at sea ship John A. Parks after transferring her provisions and

stores to Alabama. She had a cargo of lumber and Semmes remarked after

this capture," ... if I had not put some restraint on my zealous officer of the

adze and chisel, I believe he would have converted the Alabama into a

lumberman." Mid-March found the raider in the waters northeast of Brazil where

he captured and released on bond ship Punjab, from Calcutta for London.

On 23 March, off the Brazilian coast near the equator, ship Morning Star

was captured and whaling schooner Kingfisher was burned. Two days later,

and still off the coast of Brazil, ships Charles Hill and Nora

were captured, and again one is fascinated to read the vivid language which

Semmes uses to describe the capture: "It was time now for the Alabama to

move. Her main yard was swung to the full, sailors might have been seen running

up aloft, like so many squirrels, who thought they saw 'nuts' ahead, and pretty

soon, upon a given signal the top-gallant sails and royals might have been seen

fluttering in the breeze,for a moment, and then extending themselves to their

respective yard-arms. A whistle or two from the boatswain and his mates, and the

trysail sheets are drawn aft and the Alabama has on those seven-league

boots .... A stride or two, and the thing is done. First, the Charles

Hill, of Boston, shortens sail, and runs up the 'old flag,' and then the

Nora, of the same pious city, follows her example. They were both laden

with salt, and both from Liverpool."

The waters off Brazil were good hunting grounds for Alabama. On 4

April 1863, she captured ship Louisa Hatch with a large cargo of coal,

from Cardiff for Ceylon. Semmes took the prize with him in the event he failed

to make his planned contact with bark Agrippina and her replenishments at

Fernando de Noronha Island. This proved to be a correct decision, for

Agrippina did not arrive off that island. On 15 April, the whalers

Kate Cory and Lafayette were captured. Semmes took coal,

provisions, and recruited four men for his crew from Louisa Hatch and

then put her to the torch on 17 April. One week later, still operating off the

Brazilian coast, Semmes captured and burned whaler Nye with a cargo of

sperm and whale oil. Of this capture, he later wrote: "The fates seemed to have

a grudge against these New England fishermen .... This was the sixteenth I had

captured---a greater number than had been captured from the English by Commodore

David Porter, in his famous cruise in the Pacific, in the frigate Essex, during

the War of 1812." On 26 April, off Natal, he captured and burned steamer

Dorcas Prince with a cargo of coal.

--11--

The month of May 1863 was not overly fruitful. On 3 May, he captured and

burned bark Union Jack and ship Sea Lark off Brazil. Weeks later,

on 25 May, he burned ship Gildersleeve, bonded Justina off Bahai,

and put the crew of the Gildersleeve on board her. Jabez Snow with

a cargo of coal, from Cardiff to Montevideo, was captured and burned in the

South Atlantic on the 29th. June was not much more productive. On the second day

of that month, after an eight-hour chase in these same waters, bark

Amazonian was captured and burned. She was from New York for Montevideo

with a cargo including commercial mail. Ship Talisman. enroute to

Shanghai, was captured in the mid-Atlantic on 5 June. This was a most welcome

capture as Semmes notes in his log: "Received on board from this ship during the

day, some beef and pork and bread, etc., and a couple of brass 12-pounders,

mounted on ship carriages. There were four of these pieces on board, and a

quantity of powder and shot, two steam boilers, etc., for fitting up a steam

gunboat .... at nightfall set fire to the ship, a beautiful craft of 1,100

tons."

About two weeks passed before Semmes came upon another victim. She was bark

Conrad, with good sailing qualities, out of Buenos Aires for New York

with a cargo of wool and goatskins, which he captured on 20 June. He decided to

commission her as a cruiser and named her C.S.S. Tuscaloosa,

after a town in Alabama. He armed her with guns from captured

Talisman, transferred 15 of his own able crew to her, and made Acting

Lieutenant John Low her commanding officer. Low had orders to rendezvous with

the Alabama at Saldanha Bay near the Cape of Good Hope. Semmes wrote:

"Never perhaps was a ship of war fitted out so promptly before. The

Conrad was a commissioned ship, with armament, crew, and provisions on

board, flying her pennant; and with sailing orders signed, sealed, and

delivered, before sunset on the day of her capture."

That same evening he boarded English bark Mary Kendall. At the request

of her master, Semmes sent his surgeon on board to assist a seaman who had been

badly injured. The Captain in return agreed to take thirty-one prisoners,

including a woman passenger off Conrad, into Rio. About this time Semmes

decided, as he said, that he would" ... stretch over to the Cape of Good Hope."

After a few days enroute, however, it was found that weevils had contaminated

the bread supplies. He was then 825 miles from Rio and, as he said, "some little

distance to travel to a baker's shop." An unsuspecting Yankee ship, however,

furnished the answer. On 2 July Semmes captured ship Anna F. Schmidt from

Boston for San Francisco with a valuable cargo of ready-made clothing, hats,

boots, and shoes, plus a 30-day supply of bread in airtight casks, crockery,

chinaware, clocks and medicines including the "latest invention for killing bed

bugs." A full day was needed to transfer the booty to the Alabama. The

ship was burned and Semmes adds: "We then wheeled about and took the fork of the

road again,

--12--

for the Cape of Good Hope." The voyage to the Cape was quite uneventful.

However, enroute he did take ship Express from Callao for Antwerp with a

cargo of guano. The ship was burned.

In South Africa

On 30 June 1863, Semmes wrote in his journal: "It is two years to-day since

we ran the blockade of the Mississippi in the Sumter .... Two years of

almost constant excitement and anxiety, the usual excitement of battling with

the sea and the weather and avoiding dangerous shoals and coasts, added to the

excitement of the chase, the capture, the escape from the enemy, and the battle.

And then there has been the government of my officers and crew, not always a

pleasant task, for I have had some senseless and unruly spirits to deal with

.... All these things have produced a constant tension of the nervous system,

and the wear and tear of body in these two years would, no doubt, be quite

obvious to my friends at home, could they see me on this 30th day of June,

1863."

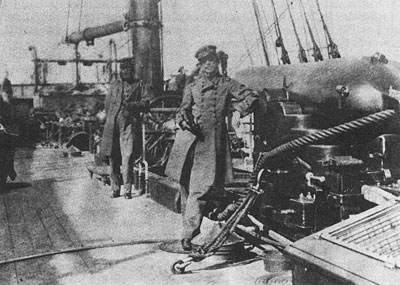

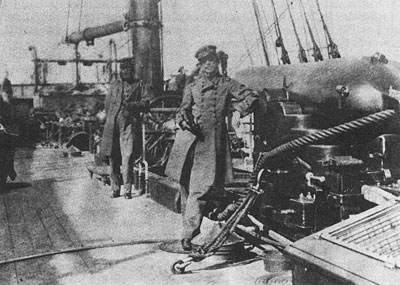

Captain

Semmes in Alabama at Cape Town

--13--

His first stop was on 28 July at Saldanha Bay, a Dutch settlement about

eighty miles northwest of Cape Town. He expected to meet bark Agrippina

there but she did not show. Commander Bulloch, on 10 July, had informed

Secretary Mallory of his decision to sell Agrippina. Although she had

made three voyages to supply the Alabama, she had lost contact with the

fast moving raider and it was too costly to maintain her as a tender.

Alabama remained at Saldanha Bay for a week, while she replenished with

fresh provisions, and the crew enjoyed hunting and fishing in the area. The stay

had an unfortunate incident. The Third Assistant Engineer was returning from a

hunt when the cock of his gun hit the gunwale and a full load of buckshot in his

chest killed him.1 At sea again and off Table Bay, Cape of Good Hope,

on 5 August he overtook and captured bark Sea Bride with a cargo of

provisions. The capture took place within view of the cheering crowds ashore. A

local newspaperman wrote: "They did cheer, and cheer with a will, too. It was

not, perhaps, taking the view of either side, Federal or Confederate, but in

admiration of the skill, pluck and daring of the Alabama, her Captain,

and her crew, who afford a general theme of admiration for the world all

over."

In Cape Town, Semmes heard news of the Battle of Gettysburg about six weeks

before. On 15 August, he left port for a month's unproductive cruise in nearby·

waters. He met the cruiser Tuscaloosa in the Angra Pequena Bay off the

west coast of Africa on 28 August and directed her to return to the coast of

Brazil.

Return to Cape Town again brought discouraging news. Vicksburg and Port

Hudson had fallen. Semmes later wrote: "This [the surrender of Vicksburg] was a

terrible blow to us. It not only lost us an army, but cut the Confederacy in

two, by giving the enemy the command of the Mississippi River ... Vicksburg and

Gettysburg mark an era in the war.... We need no better evidence of the shock

which had been given to public confidence in the South, by those two disasters,

than the simple fact, that our currency depreciated almost immediately a

thousand per cent!" He also learned that the well-armed Federal steamer U.S.S.

Vanderbilt,

in command of Commander C.H. Baldwin, had been in port looking for him.

Far Eastern Cruise

Semmes decided to move to the Far East and left Cape Town on 24 September for

his long cruise across the Indian Ocean. He

--14--

passed St. Paul's Island on 12 October and then stood up to the northward. On

4 November, he spoke to a Dutch bark and learned that U.S.S. Wyoming, a

small bark-rigged steam gunboat, (Commander David McDougal in command) was

patrolling the Sunda Straits between Sumatra and Java. Semmes knew that

Alabama was a good match for the Union gunboat. He sailed for the

Straits, but by the time he arrived, the Wyoming had departed. He did

succeed in capturing and destroying bark Amanda with a cargo of hemp and

sugar on 6 November. The clipper Winged Racer, "... a perfect

beauty---one of those New York ships of superb model, with taut, graceful masts,

and square yards, known as 'clippers'," was captured and burned on 10 November

in the Straits of Sumatra. Semmes permitted her Captain and crew to sail in

their own ship's boats for Batavia, not too far away. She had a cargo of sugar,

hides and jute. Semmes wrote: "She had, besides, a large supply of Manila [sic]

tobacco, and my sailors' pipes were beginning to want replenishing." The

following day after a long chase clipper Contest, with a cargo of

Japanese goods for New York, was captured off Gaspar Strait and destroyed.

Semmes continued his cruises to the northward and, on 3 December, arrived at the

island of Condore where he landed for supplies and remained about 2 weeks. On

leaving the island, Semmes wrote: "The homeward trade of the enemy is now quite

small, reduced, probably, to twenty or thirty ships per year, and these may

easily evade us by taking the different passages to the Indian Ocean .... there

is no cruising or chasing to be done here, successfully, or with safety to

oneself without plenty of coal, and we can only rely upon coaling once in three

months .... So I will try my luck around the Cape of Good Hope once more, thence

to the coast of Brazil, and thence perhaps to Barbados for coal, and thence---?

If the war be not ended, my ship will need to go into dock to have much of her

copper replaced, now nearly destroyed by such constant cruising, and to have her

boilers overhauled and repaired, and this can only be properly done in Europe."

He set course for Singapore where he arrived on 21 December. He noted the effect

of Confederate commerce raiding on Northern shipping in the Far East and wrote:

"The enemy's East India and China trade is nearly broken up. Their ships find it

impossible to get freights, there being in this port [Singapore] some nineteen

sail, almost all of which are laid up for want of employment ... the more widely

our blows are struck, provided they are struck rapidly, the greater will be the

consternation and consequent damage of the enemy." The U.S.S. Wyoming, as

he learned, had been in Singapore twenty days before. Semmes remained there only

3 days to coal and provision and then started his long return trip toward the

Atlantic via Cape of Good Hope. On 24 December, in the Straits of Malacca, he

captured and burned ship Texas Star with a cargo of rice. She was sailing

under the name of Marta Ban and flew British colors. Semmes noted,

however, that this "sale" was not a bonafide transaction, and hence the

destruction was legal. On Christmas day of 1863, he landed his

--15--

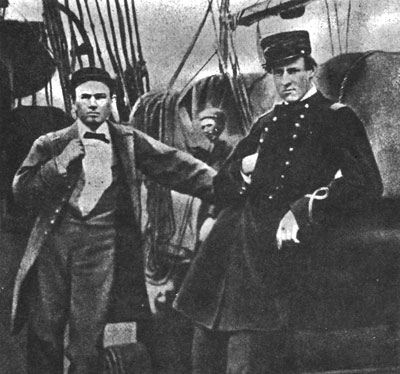

Lieutenants

Armstrong and Sinclair aboard Alabama

prisoners at Malacca. The only Christmas celebration on the Alabama

was the usual "splicing of the main-brace" by the crew. The following day ships

Sonora and Highlander, both in ballast and at anchor at the

western entrance of the Straits of Malacca, were burned. Semmes notes: "They

were monster ships, both of them, being eleven or twelve hundred tons burden."

One of the masters told the commerce raider: "Well, Captain Semmes, I have been

expecting every day for the last three years to fall in with you, and here I am

at last. . .. The fact is, I have had constant visions of the Alabama, by

night and by day; she has been chasing me in my sleep, and riding me like a

night-mare, and now that it is all over, I feel quite relieved."

Semmes next headed for Anjenga on the southwest coast of India. In passage,

on 8 January 1864, he identified himself to an English bark as the U.S.S. Dacotah in

search of the raider Alabama. The master of the bark replied, "It won't

do; the Alabama is a bigger ship than you, and they say she is iron

plated besides." Had the latter been true, the fate of the raider may have been

different. On 14 January, he captured and burned ship Emma Jane and three

days later arrived at Anjenga. He put his prisoners ashore, and he sailed for

Comoro Islands, a Mohammaden settlement near the coast of Africa, where he

arrived for provisions and relaxation on 9 February. The relaxation left

something to be desired: "There was no such thing as a glass of grog to be found

in the whole town, and as for a fiddle, and Sal for a partner---all of which

would have

--16--

been a matter of course in civilized countries---there were no such luxuries

to be thought of. They found it a difficult matter to get through with the day,

and were all down at the beach long before sunset---the hour appointed for their

coming off---waiting for the approach of the welcome boat. I told Kell to let

them go on shore as often as they pleased, but no one made a second

application."

The Alabama left Comoro Islands on 15 February and headed south

through the Mozambique Channel for Cape Town. Now the Captain confided to his

journal: "My ship is weary, too, as well as her commander, and will need a

general overhauling by the time I can get her into dock. If my poor service

shall be deemed of any importance in harrassing and weakening the enemy, and

thus contributing to the independence of my beloved South, I shall be amply

rewarded." Arriving 20 March, he learned that the British had seized C.S.S.

Tuscaloosa. Semmes protested this action to the British Admiral on the

station. The local Governor considered the seizure unjustified. The reversal did

not arrive in Cape Town until after Semmes had left and the war was almost over.

Tuscaloosa was ultimately turned over to the American Consul.

The Last Cruise

Alabama left Table Bay on 25 March and set a course to the westward.

Just outside the harbor, she passed Yankee steamer Guag Taug enroute to

China. Since the ship was inside local waters, Semmes decided to permit her to

pass in order to avoid trouble with the British. West of Cape Verde Islands on

23 April he captured and burned the Rockingham from Callao for Cork with

a cargo of guano. Semmes writes of this capture: "It was the old spectacle of

the panting, breathless fawn, and the inexorable stag-hound. A gun brought his

colors to the peak, and his mainyard to the mast .... We transferred to the

Alabama such stores and provisions as we could make room for, and the

weather being fine, we made a target of the prize, firing some shot and shell

into her with good effect and at five P.M. we burned her and filled away on our

course." Four days later east of Salvador, Brazil, Tycoon, from New York

for San Francisco, with a cargo of merchandise, including some valuable clothing

and late newspapers, met the same fate. Once again Semmes takes time to note:

"We now hailed, and ordered him to heave to, whilst we should send aboard of

him, hoisting our colors at the same time .... The whole thing was done so

quietly, that one would have thought it was two friends meeting." These proved

to be the last victims of the great raider.

Target practice on the abandoned Rockingham showed that the gunpowder

of the Alabama had badly deteriorated to the extent that only one in

three shells were exploding. Semmes recognized the condition of his ship,

equipment and personnel,for in May 1864, he said, "The poor old Alabama

was not now what she had been

--17--

then. She was like the wearied fox-hound, limping back after a long chase

.... Her commander, like herself, was well-nigh worn down. Vigils by night and

by day, the storm and the drenching rain, the frequent rapid change of climate

... and the constant excitement of the chase and capture, had laid, in the three

years of war he had been afloat, a load of a dozen years on his shoulders. The

shadows of a sorrowful future, too, began to rest upon his spirit."

It is interesting to note that on 12 May 1864 Flag Officer Barron in Paris

wrote Secretary Mallory: "To-day I have heard indirectly and confidentially that

the Alabama may be expected in a European port on any day. Ship and

captain both requiring to be docked. Captain Semmes' health has begun to fail,

and he feels that rest is needful to him. If he asks for a relief, I shall order

Commander T.J. Page to take his place in command, and shall not hesitate to

relieve the other officers if they ask for respite from sea duty after their

long, arduous, and valuable service on the sea. There are numbers of fine young

officers here who are panting for active duty on their proper element, and will

cheerfully relieve their brother officers who have so handsomely availed

themselves of the opportunities afforded them of rendering such distinguished

service to their country and illustrating the naval profession."

At Cherbourg

Semmes pressed on to his destination and arrived in Cherbourg at 1230 on 11

June 1864. He called on the French Vice Admiral Prefect Maritime and obtained

permission to land his prisoners. His request for repairs and overhaul was

referred to Paris. When the Alabama arrived at Cherbourg, William L.

Dayton, United States Minister to France, immediately protested the use of the

port by a vessel with a character "so obnoxious and so notorious." He also

relayed, through the American Vice Consul at Cherbourg, the material condition

of the Alabama to Captain Winslow of the U .S.S. Kearsarge then at

Flushing.

Kearsarge had been stationed off the coast of France with the intent

of preventing the escape of the Confederate raider Rappahannock

from Calais. The commanding officer of the Kearsarge was Captain John A.

Winslow, who had shared a stateroom with Semmes in the old Raritan. They

had fought together in the Mexican War. Both were energetic and zealous in their

respective duties. In fact, Winslow had lost the sight in one eye because he

would not take enough time ashore for treatment.

Captain Winslow sailed for Cherbourg on 13 June after telegraphing the

American Consul at Lisbon to have the U.S.S. St. Louis

join him off that port. The next day Kearsarge steamed into the harbor

and, without anchoring, sent a boat ashore with a message for the port

authorities. The Federal ship then returned to sea to

--18--

Captain

John A. Winslow, USN

--19--

take up the blockade. Semmes, through his agent and the U.S. Consul, sent a

challenge to Winslow saying: " ... My intention is to fight the Kearsarge

as soon as I can make the necessary arrangements. I hope they will not detain me

more than until tomorrow evening, or after the morrow morning at furthest. I beg

she will not depart before I am ready to go out." Captured chronometers, gold,

the ship's pay rolls and the ransom bonds he had issued were placed ashore.

Magazines and shell rooms were overhauled and guns were readied as the

Alabama prepared to meet her destiny.

On 16 June, Semmes wrote Flag Officer Barron in Paris: "The position of

Alabama here has been somewhat changed since I wrote you. The enemy's

steamer, the Kearsarge, having appeared off this port, and being but very

little heavier, if any in her armament than myself, I have deemed it my duty to

go out and engage her. I have therefore withdrawn for the present my application

to go into dock, and am engaged in coaling ship." He noted in his journal: "The

enemy's ship still standing off and on the harbor."

She Meets the Kearsarge

Between 0900 and 1000 on Sunday, 19 June, the Alabama steamed out of

Cherbourg harbor. The Kearsarge was between six and seven miles off the

coast clear of French waters. Word of

Naval

Engagement between the USS Kearsarge & the Alabama off

Cherbourg, on Sunday 19th of June 1864

--20--

the ensuing action brought multitudes of spectators to the shore. In

addition, many small craft put to sea including yacht Deerhound owned by

John Lancaster, a pro-Southern British gentleman of Lancashire. The French

ironclad Couronne also stood out with Alabama until she was beyond

the three mile limit. The Kearsarge and Alabama were quite evenly

matched: both were steam powered, just over 200 feet long. The Kearsarge

had 400 H.P.; the Alabama about 300 H.P. The complement of the

Kearsarge was 163; the Alabama, 149. The Kearsarge had

four-32 pounders, one-28 pound rifle, two powerful XI inch Dahlgren shell guns,

mounted fore and aft on pivots so they could be fired to each side. The

Alabama had six-32 pounders on broadside and two pivot guns amidships; a

100 pounder forward, and an VIII inch aft. The odds, however, favored the

Kearsarge; for the Alabama had been a long time at sea, her bottom

was foul, her crew tired and her powder poor. In addition, and unknown to

Semmes, the Kearsarge had her engine spaces protected by heavy chains

secured to the side planking. The chains were boxed over and painted the same

color as the remainder of the hull.

The sea was calm with the wind from the west. The sun was bright but a light

haze hung over the water. As Alabama steamed out to the northward, Semmes

addressed his crew before sending them to their quarters. Both Captains planned

their battle tactics to use their starboard guns and Semmes shifted a 32-pounder

to that side. This gave the ship a starboard list and, although it hampered

maneuvering, it did expose less of her side to enemy fire.

The ships closed with Alabama standing to the northward and

Kearsarge to the westward. To keep from drawing apart while using their

starboard batteries, they had to circle about a common center. Kearsarge

wheeled, as the ships approached, to bring her starboard guns to bear. The ships

were about a mile and a half apart at 1057 when Alabama opened the

action. She fired three times before Kearsarge replied. Since

Alabama's guns had the longer range, she had the initial advantage. Had

her powder been reliable, she might have won the battle in the first fifteen

minutes because a shell from her 100-pounder lodged in the wooden sternpost of

Kearsarge. It did not explode. Had it done so, it would have blown away

the steering gear of Kearsarge and, at the very least, made her

unmanageable. The effect of the "misfire" merely made the rudder harder to

handle.

Both ships continued to circle each other. It did not take Semmes long to

realize that his shots were not effective against the chain-protected hull of

Kearsarge. Semmes ordered the gunners to aim higher, and shots soon tore

away the stack and engine room hatch of Kearsarge. He tried to close the

range with the intent of boarding, but Winslow wisely avoided this tactic.

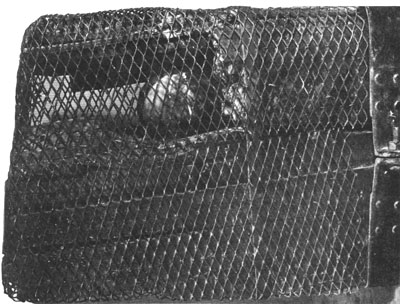

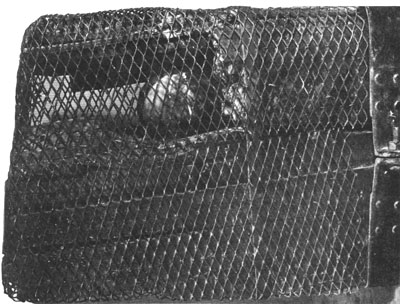

--21--

Shell

in sternpost of USS Kearsarge

After about eighteen minutes, the Dahlgrens of Kearsarge began to find

their mark and their effect was disastrous. They not only swept away everything

above deck, but fatally hulled the valiant Confederate raider. The water was

soon waist deep and she began sinking rapidly. Semmes reported: "After the lapse

of about one hour and ten minutes, our ship was ascertained to be in a sinking

condition, the enemy's shells having exploded in our side, and between decks,

opening large apertures through which the water rushed with great rapidity. For

some minutes I had hopes of being able to reach the French coast, for which

purpose I gave the ship all steam, and set such of the fore and aft sails as

were available. The ship filled so rapidly, however, that before we had made

much progress, the fires were extinguished in the furnaces, and we were

evidently on the point of sinking. I now hauled down my colors to prevent the

further destruction of life, and dispatched a boat to inform the enemy of our

condition."

During the battle Kearsarge fired about 173 shots and Alabama

almost twice as many, only twenty-eight of which hit Kearsarge. When

Semmes ordered: "Every man save himself who can!" to be piped, only two of

Alabama's boats were usable. Most of the crew leaped overboard. Semmes

entrusted his papers to a sailor who was a good swimmer, and hurled his sword

into the sea before he jumped. Alabama sank stern first in about 250

fathoms at 1250. Yacht Deerhound picked up 40 survivors, including Semmes

and thirteen officers. French pilot boats came out

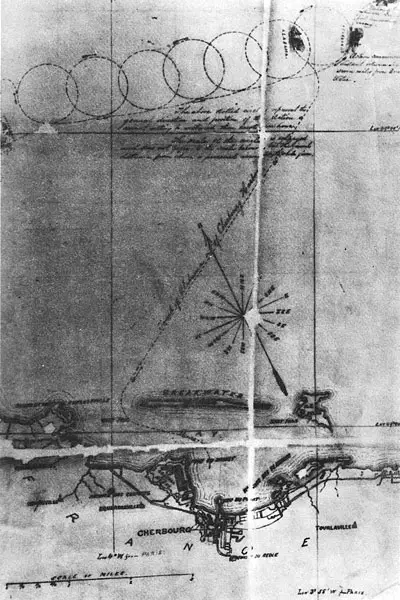

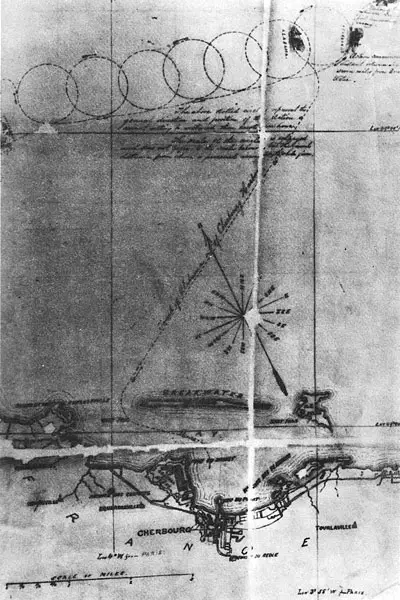

--22--

Captain

Winslow's track chart of the engagement

--23--

to assist in the rescue. Twenty-one wounded were sent to Kearsarge.

The ship's doctor refused to accompany them and was drowned. It is believed that

nine men were killed in the battle and another ten were drowned.

The Deerhound took Semmes and other rescued crew members, including

the seaman to whom Semmes had entrusted his papers, into Southampton, England.

The action of Deerhound, and the fact that Semmes and his men were

received with enthusiasm, gave rise to much criticism and comment in both

England and the United States. As an indication of the sentiment that was

prevailing among certain groups, it is interesting to note that the Junior

United Service Club in London, of which many officers of the British Army and

Navy were members, presented Semmes with a " ... magnificent sword, which had

been manufactured to their order in London, with suitable naval and Southern

devices." The battle stimulated the imagination of writers; numerous songs and

stories appeared about the celebrated sea battle fought off the French coast by

two American ships---one Union, one Confederate.

In Summary

Certainly the cruise of Alabama from August 1862 to June 1864 was a

truly remarkable performance for ship and crew. She

Surrender

of Alabama to Kearsarge

--24--

Sword

presented to Captain Semmes by British officers

had not touched a home port during her entire career. She put into Cherbourg

with all her original officers except the Paymaster who had been put ashore in

Jamaica and the Third Engineer who had been killed accidentally in Saldanha Bay.

Additionally, a large part of her original crew were still with her. Semmes

notes: " ... how sedulously we guarded against intemperance, at the same time

that we gave the sailor his regular allowance for grog." As many as 2,000

prisoners had been confined for varying periods and not one had been lost by

disease. The ship was self-supporting while cruising in all latitudes.

She was a taut, effective and efficient raider and Semmes justly reminded his

men before her last battle: "You have destroyed, and have driven for protection

under neutral flags, one-half of the enemy's commerce, which, at the beginning

of the war, covered every sea."

Alabama had captured and burned at sea fifty-five Union merchantmen

valued at over four and one-half million dollars; had bonded ten others to the

value of five hundred sixty-two thousand dollars. Another prize, Conrad,

was commissioned C.S.S. Tuscaloosa, which struck at Northern shipping.

The U.S. Navy also felt Alabama's sting when she sank U.S.S.

Hatteras off Galveston.

For his victory, Captain Winslow of Kearsarge was given a vote of

thanks by the Congress and promoted to Commodore on 19 June 1864.

--25--

The Captain's Last Eleven Years

It was several months after the loss of his ship before Captain Semmes was

able to arrange for his return to the Confederacy from England. Through the

kindness of his friends, and incident to the sympathetic attitude of some of the

citizens of that country toward the South, Semmes was able to settle his

Alabama affairs and spent some time touring the Continent. He finally

sailed on the steamer Tasmanian, on 3 October 1864, for Havana via St.

Thomas. It is interesting to note his concern about this voyage, for he said,

"The very mention of my name had as yet the same such effect upon the Yankee

Government as the shaking of a red flag before the blood-shot eyes of an

infuriated bull."

Before he left England, Semmes recalled: "I considered my career upon the

high seas closed by the loss of my ship, and had so informed Commodore Barron,

who was our Chief of Bureau in Paris." Nevertheless, he was still to play an

important role in the final war efforts of the Confederacy. He made his way by

ship into Mexico and, assisted by the Commandant at Brownsville, Texas, finally

reached his native soil. A hero's reception was afforded him and special coach

transportation was provided to take him to Mobile where he arrived on 27

November 1864. After some time to recuperate and get his affairs in order, he

proceeded to Richmond and reported to President Davis. The Confederate Congress

honored him with a vote of thanks. Appointed to the rank of Rear Admiral in the

Confederate Navy, on 10 February 1865, he was given command of the James River

Squadron, 18 February. In April, when the fall of Richmond was imminent, he was

ordered to destroy his ships to prevent their capture and to form his crews of

about 400 men into a Naval Brigade which was to join President Davis and the

Confederate cabinet in Danville. Upon his arrival there, on 4 April, he was

authorized by President Davis to act in the capacity of a Brigadier General in

the Army. He took part in the final battle in the area and surrendered with

General Josh E. Johnson on 1 May 1865.

Semmes was arrested in Mobile on 15 December 1865, accused of piracy. He was

held without trial until 7 April 1866 when he was released. He subsequently

taught in what is now Louisiana State University, edited a newspaper in Memphis,

and spent some time in Mobile writing, lecturing, and teaching law. Admiral

Semmes died in Mobile on 30 August 1877 at the age of 68. His career of service

at sea, both in the U.S. Navy before the Civil War and in the Confederate Navy,

gave solid testimony to the words he addressed to President Jefferson Davis:

"Whatever else may be said of me, I have, at least, brought no discredit upon

the American name and character."

Source:

Naval Historical Foundation

Chief

of Naval Operations

02 August 2007