It is written in some history books that a number of circumstances

led the United States into civil war, but this is not really true. A number of

circumstances may have contributed to the development of unfriendly feelings

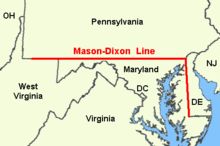

between those white people who lived in the States south of the Mason-Dixon

Line and those who lived north of it, but the mere fact that disagreements

exist between different groups of people in a particular society does not

usually trigger in the people such anger and resentment that they throw

themselves into a war. It is written in some history books that a number of circumstances

led the United States into civil war, but this is not really true. A number of

circumstances may have contributed to the development of unfriendly feelings

between those white people who lived in the States south of the Mason-Dixon

Line and those who lived north of it, but the mere fact that disagreements

exist between different groups of people in a particular society does not

usually trigger in the people such anger and resentment that they throw

themselves into a war.

Take, for example, the situation in the United States today, where we

have an almost equal division (in terms of population) between what are called

"blue" and "red" States, with millions of people on

opposite sides arguing loudly about all kinds of matters, from issues of family

values to economic issues such as taxes, social security, and health care.

Though the arguments are at times loud and heated, and have been going on now

for years, we as a people all agree we are not going to war with ourselves over

them. The reason for this, is simply that, though loud and heated, these

arguments are based more on abstractions than on universal feelings

of antagonism between distinct and unified sections of the country. No,

what caused the American Civil War was simply the plain fact that, between 1776

and 1860, the institution of slavery existed in the United States south of the Mason-Dixon Line. Take, for example, the situation in the United States today, where we

have an almost equal division (in terms of population) between what are called

"blue" and "red" States, with millions of people on

opposite sides arguing loudly about all kinds of matters, from issues of family

values to economic issues such as taxes, social security, and health care.

Though the arguments are at times loud and heated, and have been going on now

for years, we as a people all agree we are not going to war with ourselves over

them. The reason for this, is simply that, though loud and heated, these

arguments are based more on abstractions than on universal feelings

of antagonism between distinct and unified sections of the country. No,

what caused the American Civil War was simply the plain fact that, between 1776

and 1860, the institution of slavery existed in the United States south of the Mason-Dixon Line.

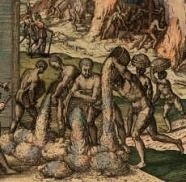

Slavery—the situation where a person is forced to serve or labor

against his or her will for another person—has existed among human cultures

since almost the beginning of recorded time. It existed in ancient Greece and Rome and it still exists today in Africa. It seems to have its origin in the

idea that the victor in war is entitled to treat the vanquished as slaves, to

force those captured in battle to labor indefinitely for the benefit of the

victor. Slavery—the situation where a person is forced to serve or labor

against his or her will for another person—has existed among human cultures

since almost the beginning of recorded time. It existed in ancient Greece and Rome and it still exists today in Africa. It seems to have its origin in the

idea that the victor in war is entitled to treat the vanquished as slaves, to

force those captured in battle to labor indefinitely for the benefit of the

victor.

In the fifteenth century, after Columbus discovered America, the

Spanish Government seized upon this idea as justification to enslave the entire

native population, forcing the "Indians" to labor to their deaths in

the silver and gold mines and on the plantations the Spaniards developed in the

New World. During the two hundred years that Spain ruled most of America, the Indian population was reduced to mere thousands by the harshness of the

slavery system and, in consequence, Spain turned to Africa to find a

replacement labor force. This resulted in the capture and transportation to the

New World of millions of Africans who came in chains on board Spanish ships.

In the wake of Spain's exploitation of America's resources, much less Africa's, England slowly began to establish colonies on the eastern

seaboard of North America. Virginia was the first of these colonies and, to

hurry her economic development, the English monarchs decreed that slavery was

lawful. As additional colonies came into being—Massachusetts, New York,

Pennsylvania, Georgia, and the Carolinas, to mention the first few—the royal

decree was applied to them and very soon Africans were introduced into the

colonies as slaves, so that by the time of the American Revolution there were

populations of African slaves in each of them, supplied by New England ships

carrying on the slave trade where Spain left off.

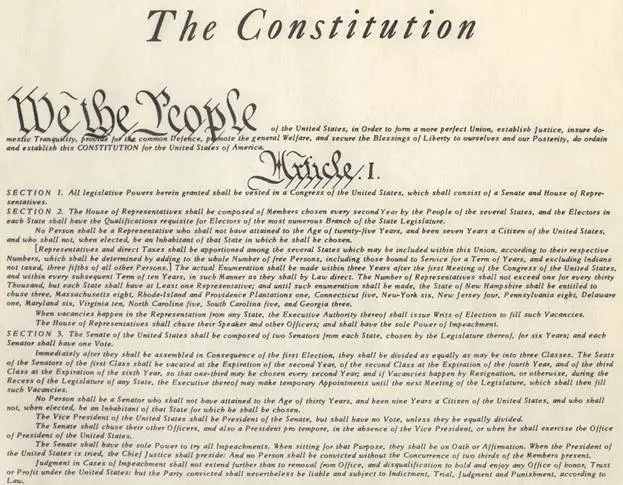

When the American colonies declared their independence from England, in 1776, and then entered into the compact we know as the United States

Constitution in 1789, they became recognized as States by the nations of Europe; and, as such, they retained, each in their own right, full control of their

domestic policies. Since slavery had been long recognized, under the law of

nations, and actually existed in each of the United States, the institution was

recognized by the Constitution of the United States. Without such recognition

the United States of 1789 could never have been formed.

The United States Constitution

Article I

Section 2: "Representatives shall be appropriated among the several States according to their respective numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole number of free persons, three fifths of all other persons." (edited for brevity)

Article II

Section 9: "The migration or importation of such persons as any of the States now existing shall think proper to admit, shal not be prohibited by the Congress prior to the year one thousand eight hundred and eight." (edited for brevity)

Article IV

Section 2: "No person held to service or labor in one State, under the laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in consequence of any law or regulation therein, be discharged from such service or labor, but shall be delivered up upon claim of the party to whom such labor is due."

Note: The historians, in masking the Constitution's recognition of the States' domestic policy of slavery, harp on the fact that the word "slavery" is not written in it. One would have to be a dunce, however, not to recognize who the founders meant by "other persons," and "such persons," and a "person held to labor." |

This fact—slavery's recognition in the Constitution—ultimately

resulted in the occurrence of the Civil War: for slowly at first, then very

rapidly, a great feeling of antagonism against the slave States welled up in

the minds of most of the white people living in the States north of the

Mason-Dixon Line. The basic reason for this, was that white immigrants from

Europe poured into the northern States, exploding the white population of those

States and creating great pressure upon the Federal Government to push as

rapidly as possible development westward across the Great Plains to the Pacific

Ocean. At the same time, the slave-owners were moving westward in search of fresh

lands for their cotton plantations. This generated an increasingly violent competition

between the two sections for access to the West, triggered by the prejudice of the great majority of the white people of the North who did not want to

live in a community that included Africans, whether free or not. (The extent of the prejudice against Africans can be seen in the speeches of the senators recorded in the congressional record of the thirty-seventh congress. See, for example, What Happened in March 1862)

White

Immigrants Arriving

The antagonism between the two sections, generated by the

issue of equal access to the territories of the United States, first manifested

itself in the political competition between two parties: on the one hand there

was the Democratic Party, controlled to a large extent by Southerners, and on

the other the Whig, and later, Republican Party, controlled by Northerners.

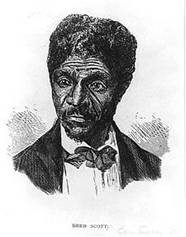

Over a period of about thirty years, this political competition for control of

development in the territories resulted in a series of compromises and,

ultimately, led to the notorious Supreme Court decision known as Dred

Scott.

In 1819, at the time of Missouri's admission to the Union as a State, for example, the two sides entered into the historic Missouri Compromise

which had the effect of dividing the territories into free labor and slave

labor zones. This compromise was continued in modified form by the Compromise

of 1850 and, yet again, by the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act. Then, with a great

shock, the system of compromise collapsed suddenly when the Supreme Court

ruled, in Dred Scott, that southerners had as equal a right to go

with their slaves anywhere in the territories as did northerners.

Now the antagonism, previously played out in oratory on the floors

of the Senate and House of Representatives, and in lawsuits before the courts, became public

displays of physical violence, most notably by John Brown, a terrorist with a

passion for doing crazy things. Brown appeared in the territory of Kansas, in about 1857, and, with a motley band of killers, roamed the  countryside murdering families of Southern settlers in

their sleep. Later, in 1859, motivated by a crazy scheme to incite the slaves

to insurrection, Brown appeared at Harper's Ferry, Virginia, and occupied the

Federal Arsenal, killing several people in the process. Investigation into

Brown's affairs proved that well-known abolitionists, from Ohio

and New England, had financed Brown's activities and this nailed down the

conviction in the South that as soon as the Democratic Party lost majority

control in Congress and a Republican took possession of the Executive Department

of Government the people of the South would be barred from sharing in the

development of the West and would find themselves effectively locked up alone

with the Africans. Feeling isolated and unwanted, the people of the South were

swept like a torrent to the consensus it was time the sections were separated. countryside murdering families of Southern settlers in

their sleep. Later, in 1859, motivated by a crazy scheme to incite the slaves

to insurrection, Brown appeared at Harper's Ferry, Virginia, and occupied the

Federal Arsenal, killing several people in the process. Investigation into

Brown's affairs proved that well-known abolitionists, from Ohio

and New England, had financed Brown's activities and this nailed down the

conviction in the South that as soon as the Democratic Party lost majority

control in Congress and a Republican took possession of the Executive Department

of Government the people of the South would be barred from sharing in the

development of the West and would find themselves effectively locked up alone

with the Africans. Feeling isolated and unwanted, the people of the South were

swept like a torrent to the consensus it was time the sections were separated.

No sooner had the Republican Party's presidential candidate,

Abraham Lincoln, been elected President than, one by one, South Carolina and

the Gulf States seceded from the Union. These States joined together and formed

a new union called the Confederate States of America. They elected Jefferson

Davis, previously a United States Senator representing the State of Mississippi, as their President.

As this occurred, the Federal forts and arsenals located

within the seceded States were seized by the Confederate Government and the

arms and munitions stored there were used to build an army, the mission of

which was to defend the Confederacy against attack by Lincoln's government. In response,

as soon as Abraham Lincoln was sworn into office on March 4, 1861, he immediately set to work to orchestrate an incident that would incite the people of

the North to allow him to use the war power to conquer the

Confederate States of America.

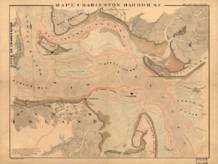

Between the date of Lincoln's election, in November 1860, and his

inauguration, in March 1861, the previous Administration had entered into an

agreement with the Governor of South Carolina, not to attempt to reinforce the

army garrison at Fort Sumter, located inside Charleston Harbor; in exchange for

this the Governor promised to provide the garrison with food supplies. Between the date of Lincoln's election, in November 1860, and his

inauguration, in March 1861, the previous Administration had entered into an

agreement with the Governor of South Carolina, not to attempt to reinforce the

army garrison at Fort Sumter, located inside Charleston Harbor; in exchange for

this the Governor promised to provide the garrison with food supplies.

Upon assuming office, President Lincoln publicly went about the

process of organizing a naval fleet of warships, accompanied by steamers

carrying infantry troops, and sent it to sea, on April 6, 1861, with the apparent mission of forcing an entrance into the harbor and

reinforcing the fort. Upon sighting lights at sea, the early morning of April

12, Confederate General Pierre Beauregard assumed Lincoln's warships were

arriving, and upon the authority of the Confederate War Department, ordered the

bombardment of the fort. The bombardment lasted many hours and the fort was

heavily damaged, though no one was killed. The garrison's commander, Major

Robert Anderson, seeing no point to continuing resistance, surrendered the

garrison on April 14, 1861. Upon assuming office, President Lincoln publicly went about the

process of organizing a naval fleet of warships, accompanied by steamers

carrying infantry troops, and sent it to sea, on April 6, 1861, with the apparent mission of forcing an entrance into the harbor and

reinforcing the fort. Upon sighting lights at sea, the early morning of April

12, Confederate General Pierre Beauregard assumed Lincoln's warships were

arriving, and upon the authority of the Confederate War Department, ordered the

bombardment of the fort. The bombardment lasted many hours and the fort was

heavily damaged, though no one was killed. The garrison's commander, Major

Robert Anderson, seeing no point to continuing resistance, surrendered the

garrison on April 14, 1861.

Instantly upon this happening, President Lincoln, without

waiting for Congress to get into session, called upon the loyal State governors

for use of their State militias for ninety days—his purpose being to "suppress

the insurrection and enforce the laws of the United States." Almost ninety

days later, Lincoln's Army, under the command of

Brigadier-General Irwin McDowell, attacked the Confederate force defending Virginia, at Bull Run.

Written by:

Joe Ryan

Expanded article "Causes of the Civil War"

Class Exercise

To find the ultimate

cause of the Civil War, it is necessary to look beyond the mere fact that

slavery existed in the United States and think about what actually was at the

core of the dispute over the existence of slavery in the United States.

The people of the United States had eighty years to solve the problem of slavery. Why were they not able to

solve it without going to war with themselves? Given the history of the times,

it was becoming increasingly obvious to all that slavery was a practice that,

for a variety of reasons, the country could no longer sustain. What is it that

prevented them, then, from simply sharing in the economic and social burdens

freedom for the slaves clearly entailed? It is obvious that the slaves might

have been freed, in exchange for some kind of economic compensation to the

slave States, and their population dispersed throughout the United States, each

State taking into its community some portion of the freed Africans. What

prevented the people of the United States from doing this?

Source Materials

John Rives, 1862, The Congressional Record: Second Session of the Thirty-Seventh Congress of the United States Alexander H. Stephens, A Constitutional View Of The War Between the States (1868) Natonal Publishing Co.

Joe Ryan What Happened in March 1862

Joe Ryan What Happened in April 1862

W.E.B. DuBois, The

Negro, Henry Holt & Co. 1915

W.E.B. Dubois, Souls of Black Folk, Barnes & Noble 2003

James Baldwin, Margaret Mead, A Rap on Race, J.B. Lippincott & Co. 1971

Bruce Catton, Mr.

Lincoln's Army, Doubleday & Co. 1956

Cause of the War-Students' Zone

Article Comments

Anne writes,

Dear Mr. Ryan:

I appreciate your effort to shed light on the truth that many people do not want to accept. Every "textbook cause" of the Civil War boils right down to slavery. I hope that one day we will have a more honest approach to our history as a nation.

Joe Ryan Replies:

Yes, as the lyric goes—"History hides the truth of our Civil War." Certainly the presence of slaves in America was the point upon which the war turned; but what is hidden by the pulp history fed to youngsters in our schools is the quite indisputable fact that Northern white men―Abraham Lincoln included—did not want to share their world equally with Africans, under any circumstances. The amazing thing is that, despite this deep feeling, once the white men of America wrestled with themselves in what became such a relentless, horrible war, the pain of it caused them to let the Africans in. One hundred and fifty years later, though not perfect yet, we have the only nation on earth―the most powerful one at that—which strives now to make racial equality the norm.

Mrs. Guyson writes,

Dear Mr. Ryan:

My son is 15 and a sophomore in high school. He announced to me this morning that "I need proof that the Civil War was about slavery." When I asked why, he told me that his teacher says it was all about states rights, taxes, and the Federal Government getting too powerful.

Now, I was born and raised in Texas, and I was taught the same dribble that my son's teacher was asserting. Not until I was an adult and began reading on my own did I understand the truth—that the Civil War was truly about slavery and racism, and so much of that racism still exists in some parts of the country that many cannot recognize the truth about what caused the Civil War.

I suggested to my son that he look at the content available on americancivilwar.com as a source where an objective view point could be found and he went off to examine the content on his own. I want to offer a thank you for the excellent material the site provides. I was happy to find it and be able to arm my son with good, solid proof that his history teacher is wrong.

Mrs. Guyson

Joe Ryan Replies:

Dear Mrs. Guyson:

I certainly appreciate your very kind note. I agree completely with your assessment about the educational value of the study plan regarding the Civil War that is offered by many high school curriculums today. Americancivilwar.com offers two pieces entitled Cause of the Civil War, one written with high schoolers in mind, the other written for those at a higher educational level. Both pieces emphasize that white racism, generally, was the core "cause" of the American Civil War—a racism that implicates the white people of the North equally with the white people of the South in causing the Civil War. The best objective evidence I offer of the truth of this statement can be found in the speeches the Northern senators and representatives made on the floor of their respective chambers during the second session of the Thirty-Seventh Congress of the United States. (See, for example, the articles titled, What Happened in March, April, and May 1862.)

Best Regards,

Joe Ryan

Mrs. Burke writes,

Dear Mr. Ryan:

I am not a teacher but a parent. My son has to write a report on the causes of the Civil War. He is in the seventh grade. We found the article, Cause of the Civil War, as we were searching the internet for information. He has to have a bibliography and we were wondering when this article was written; was it part of a book?

Thanks for making this topic more understandable to him.

Blessings,

Mrs. Burke

Joe Ryan Replies,

Dear Mrs. Burke:

The piece was written by me; it replaced a stock article the webmaster had appropriated years ago from the Federal Government's Park Service website. The latter article depends for its point on a cluster of abstractions; a cotton gin here, a tariff dispute there, with only a passing reference to the institution of slavery as sanctioned by the United States Constitution of the time.

Best Regards,

Joe Ryan |

Robert E. Lee and his Drummer Boy

|