Kindle Available Rose O'Neale Greenhow, Civil War Spy Fearless spy for the Confederacy, glittering Washington hostess, legendary beauty and lover, Rose Greenhow risked everything for the cause she valued more than life itself |

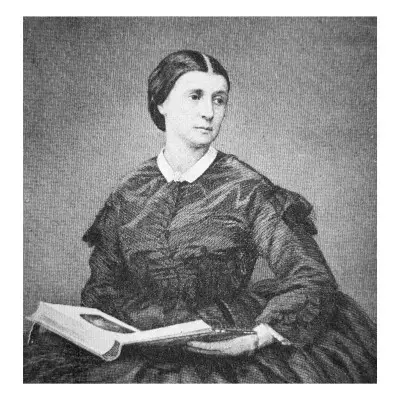

Rose O'Neal Greenhow, 1817-1864

|

|

|

|

| Among her accomplishments was the ten-word secret message she sent to General Pierre G.T. Beauregard which ultimately caused him to win the battle of She was imprisoned for her efforts first in her own home and then in the Old Capital Prison. Despite her confinement, Greenhow continued getting messages to the Confederacy by means of cryptic notes which traveled in unlikely places such as the inside of a woman's bun of hair. After her second prison term, she was exiled to the Confederate states where she was received warmly by President Jefferson Davis. Her next mission was to tour Britain and France as a propagandist for the Confederate cause. Two months after her arrival in London, her memoirs were published and enjoyed a wide sale throughout the British Isles. In Europe, Greenhow found a strong sympathy for the South, especially among the ruling classes. During the course of her travels she hobnobbed with many members of the nobility. She was received at the court of Queen Victoria and became engaged to the Second Earl Granville. In Paris, she was received into the court of Napoleon III and was granted an audience with the Emperor at the Tuileries. In 1864, after a year abroad, she boarded the Condor, a British blockade-runner which was to take her home. Just before reaching her destination, the vessel ran aground at the mouth of the Cape Fear River near Wilmington, North Carolina. In order to avoid the Union gunboat that pursued her ship, Rose fled in rowboat, but never made it to shore. Her little boat capsized and she was dragged down by the weight of the gold she received in royalties for her book. In October 1864, Rose was buried with full military honors in the Oakdale Cemetery in Wilmington. Her coffin was wrapped in the Confederate flag and carried by Confederate troops. The marker for her grave, a marble cross, bears the epitaph, "Mrs. Rose O'N. Greenhow, a bearer of dispatchs to the Confederate Government." |

Confederate Women Monument Mississippi 9 in. x 12 in. AllPosters.com |

Rose O'Neal Greenhow 24 in. x 24 in. Buy at AllPosters.com |

Confederate Spies at Large: The Lives of Lincoln Assassination Conspirator Tom Harbin And Charlie Russell The most wanted of all Confederate agents, was also one of the leaders in the plot to kill Abraham Lincoln |

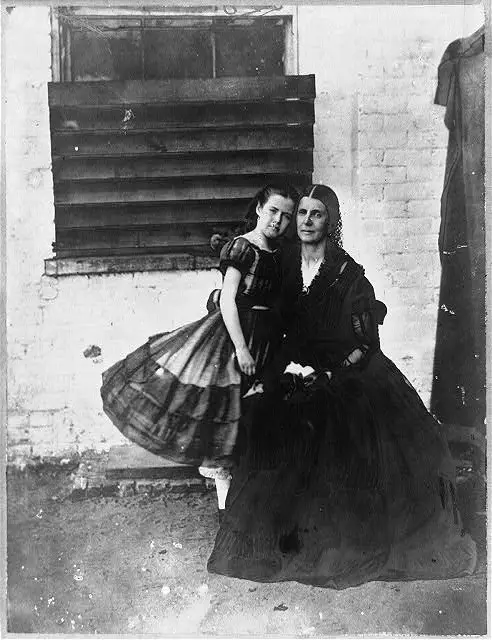

Rose Greenhow and Daughter photographed between 1861 and 1864 |

A Very Violent Rebel: The Civil War Diary of Ellen Renshaw House The Siege of Knoxville (November 1863) is covered and Sutherland's footnotes make for good history |

|

Kindle Available Women and the American Civil War An Annotated Bibliography The first reference work to draw together the stories and studies of women in the American Civil War, this annotated bibliography offers access to the literature that documents the history of women who experienced the war, changed it, and were changed by it. Offering nearly 800 entries DVD  Women And The Civil War The many contributions of women in both the North and South are presented in this DVD program describing their roles on and near the momentous battles of the American Civil War  Sanctified Trial: The Diary of Eliza Rhea Anderson Fain, a Confederate Woman in East Tennessee The Diary of Eliza Rhea Anderson Fain Kindle Available  My Story of the War : a Woman's Narrative of Four Years Personal Experience as Nurse in the Union Army |

Sanctified Trial: The Diary of Eliza Rhea Anderson Fain, a Confederate Woman in East Tennessee The Diary of Eliza Rhea Anderson Fain |

Kindle Available Harriet Tubman: Imagining a Life: A Biography Travel with Tubman along the treacherous route of the Underground Railroad. Hear of her friendships with Frederick Douglass, John Brown, and other abolitionists. |

Kindle Available Rose O'Neale Greenhow, Civil War Spy Fearless spy for the Confederacy, glittering Washington hostess, legendary beauty and lover, Rose Greenhow risked everything for the cause she valued more than life itself |

Loving Mr. Lincoln: The Personal Diaries of Mary Todd Lincoln Chronicles life, love, and daily struggles with Abraham in their 26 years together. In frank, haunting journal entries, Mary describes the pain she felt when Abraham left her at the altar, when her sons died, and when Abraham's political career seemed to be at an end |

Kindle Available The War-Time Journal of a Georgia Girl, 1864-1865 Eliza Andrews' diary is more cogent than any novel about the Civil War. General Sherman laid a track, and ELiza had to follow his footsteps through Georgia. Her insights into war and the havoc it wrought in the South are accompanied by her own editorial comments forty-four years later |

Kindle Available When Will This Cruel War Be Over? A Confederate girl in Virginia, in 1864, Emma Simpson writes about the hardships of growing up during a turbulent time |

A Girl's Life in Virginia Before the War First published in 1895. An engrossing eyewitness account of antebellum plantation life as it really was |

Record of the Actual Experiences of the Wife of a Confederate Officer The author tells of her many travels across the war-torn South, capture behind enemy lines, encounter with Belle Boyd, friendship with General J. E. B. Stuart, and the devastation suffered by the citizens of Richmond in the last days of the Confederacy. |

Freedom Train: The Story of Harriet Tubman Harriet escaped North, by the secret route called the Underground Railroad. Harriet didn't forget her people. Again and again she risked her life to lead them on the same secret, dangerous journey. |

Kindle Available The Glory Cloak: A Novel of Louisa May Alcott and Clara Barton From childhood, Susan Gray and her cousin Louisa May Alcott have shared a safe, insular world of outdoor adventures and grand amateur theater -- a world that begins to evaporate with the outbreak of the Civil War. Frustrated with sewing uniforms and wrapping bandages, the two women journey to Washington, D.C.'s Union Hospital to volunteer as nurses. |

Clara Barton Founder of the American Red Cross Young Clara Barton is shy and lonely in her early days at boarding school. She is snubbed by the other girls because she doesn't know how to talk to them. But when she gets an opportunity to assist the local doctor, her shyness disappears, and Clara begins to discover her true calling as a nurse. |

Grace's Letter to Lincoln Many important details of the time period help to make the reader understand what life was like then. It also includes photos of the actual letters written between Grace and Mr. Lincoln |

Clara Barton Spirit of the American Red Cross Ready To Read - Level Three Clara Barton was very shy and sensitive, and not always sure of herself. But her fighting spirit and desire to help others drove her to become one of the world's most famous humanitarians. Learn all about the life of the woman who formed the American Red Cross. |

Day Of Tears Through flashbacks and flash-forwards, and shifting first-person points of view, readers will travel with Emma and others through time and place, and come to understand that every decision has its consequences, and final judgment is passed down not by man, but by his maker. |

Kindle Available The Civil War Introduces young readers to the harrowing true story of the American Civil War and its immediate aftermath. A surprisingly detailed battle-by-battle account of America's deadliest conflict ensues, culminating in the restoration of the Union followed by the tragic assassination of President Lincoln |

Kindle Available A Yankee Girl at Fort Sumter Tale of a girl and her family from Boston living in Charleston, SC during the months leading up to the beginning of the Civil War by the attack on Fort Sumter. The reader senses the inhumanity of slavery through Sylvia's experiences. |

Turn Homeward, Hannalee During the closing days of the Civil War, plucky 12-year-old Hannalee Reed, sent north to work in a Yankee mill, struggles to return to the family she left behind in war-torn Georgia. "A fast-moving novel based upon an actual historical incident with a spunky heroine and fine historical detail."--School Library Journal. |

My Brothers Keeper Virginia Dickens is angry. Her father and brother Jed have left her behind while they go off to Uncle Jack's farm to help him hide his horses from Confederate raiders. It's the summer of 1863 and Pa and Jed believe 9-year-old Virginia will be out of harm's way in the sleepy little town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. |

I Thought My Soul Would Rise and Fly: The Diary of Patsy, a Freed Girl, Mars Bluff, South Carolina 1865 Not only is 12-year-old Patsy a slave, but she's also one of the least important slaves, since she stutters and walks with a limp. So when the war ends and she's given her freedom, Patsy is naturally curious and afraid of what her future will hold. |

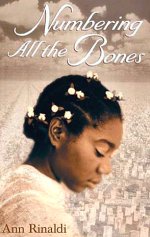

Numbering The Bones The Civil War is at an end, but for thirteen-year-old Eulinda, it is no time to rejoice. Her younger brother Zeke was sold away, her older brother Neddy joined the Northern war effort,. With the help of Clara Barton, the eventual founder of the Red Cross, Eulinda must find a way to let go of the skeletons from her past. |

| Search AmericanCivilWar.com |

| Enter the keywords you are looking for and the site will be searched and all occurrences of your request will be displayed. You can also enter a date format, April 19,1862 or September 1864. |