JEB Stuart’s Ride Around The Union Army: 1863

Events leading up to the Battle of Gettysburg

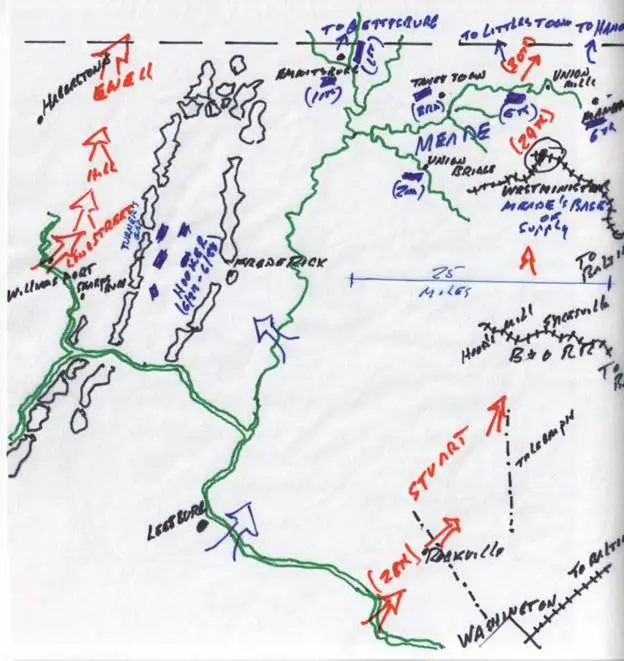

In the aftermath of General Lee’s return to Virginia from Gettysburg much controversy raged over Stuart’s role, in the public’s perception that the campaign had been a failure. Stuart was criticized for taking his column of troopers east and passing the Potomac to the right of Hooker who was then moving his army northward toward Frederick. Stuart’s case wasn’t helped by the several sequential reports General Lee’s staff prepared and Lee apparently signed. General Lee’s first report, directed by letter to President Davis on July 4th, from the field at Gettysburg, was straightforward enough. He said merely: “After the rear crossed the Potomac, Ewell pushed on to Carlisle and York. The other two corps closed up on Chambersburg, and soon afterward intelligence was received that the army of Hooker was advancing. Our whole force was directed to concentrate at Gettysburg.” Lee’s second report, filed on July 31, 1863, was likewise reasonably straightforward about his mindset and plan of operation: “It was thought the corresponding movements of the enemy, to which those contemplated by us would probably give rise, might offer a fair opportunity to strike a blow. . . .” So far, the reader cannot be confused as to what Lee meant to do—he meant to bring his corps together to fall on the enemy at or near Gettysburg. By 1864, though, the public and political pressures apparently induced him to fabricate a different explanation of his offensive plan. In Lee’s second report, as the explanation why he ordered Ewell to send Early to York, it was stated that “no report had been received that the enemy had crossed the Potomac and the absence of cavalry rendered it impossible to obtain accurate information. In order, however, to retain [the enemy] on the east side of the mountains, after [they] should enter Maryland, and thus leave open our communications with the Potomac through Hagerstown and Williamsport, Ewell had been instructed to send a division eastward from Chambersburg. Early proceeded as far as York.” The reason given in this second report, for sending Early to York, changed dramatically in the third report Lee signed off on. “It was expected,” it reads, “that as soon as the enemy should cross the Potomac, Stuart would give notice of its movements and nothing having been heard from him since our entrance into Maryland, it was inferred that the enemy had not yet left Virginia. Orders were, therefore, issued to move to Harrisburg. . . The expedition to York was designed in part to prepare for this undertaking by breaking up the railroad and seizing the bridge over the Susquehanna at Wrightsville.” (Neither reason given for Early marching to York is the truth.) Suddenly, the public is being told that Lee, thinking he had the time, and apparently the means, planned on crossing the Susquehanna in order to capture Harrisburg, not draw the enemy into a general battle at Gettysburg, but the surprise of the enemy’s presence threatening the army’s communications forced him into the battle of Gettysburg.Yet, when the evidence is marshaled in its entirety and examined objectively, this story, as well as the business about Lee’s communications with the Potomac, becomes incredible. With the new story, the public eye turned on Stuart with an angry glare, as Lee reported his reason for moving his army east of the mountains was because, not having cavalry, it was “impossible to ascertain the enemy’s intentions” and so to deter the enemy from moving into the Cumberland Valley, “it was determined to concentrate the army east of the mountains.” The objective facts of the matter do not support this explanation. At the time he was moving his army from Virginia to Frederick, on June 25 and 26, Hooker assumed the front of Lee’s army, then reported in the Cumberland Valley, would turn toward the South Mountain and pass through Turner’s Gap to take possession of Frederick. In fact, Lee’s strategic plan, formulated as early as the fall of 1862, was to move the main body of the Rebel army to the Cashtown Gap and later, as the three divisions of Ewell’s corps collapsed on Gettysburg, concentrate at that place and attack and disperse Hooker’s advance, driving it back toward the Mason-Dixon line. As Lee’s military secretary, A.L. Long wrote in 1885: before Lee left the Rapidan his plan of operation “was fully matured, and with such precision that the exact locality was indicated on his map. This locality was the town of Gettysburg.” (See, A.L. Long, Memoirs of General Lee (J.M.Stoddard & Co., 1885) Once the pressure of the three divisions of Ewell’s corps shattered the Union advance at Gettysburg, Lee meant to rush down the Emmitsburg road, to turn the enemy’s left flank at Pipe Creek, forcing them to retreat toward the forts at Washington while he moved on to Frederick.

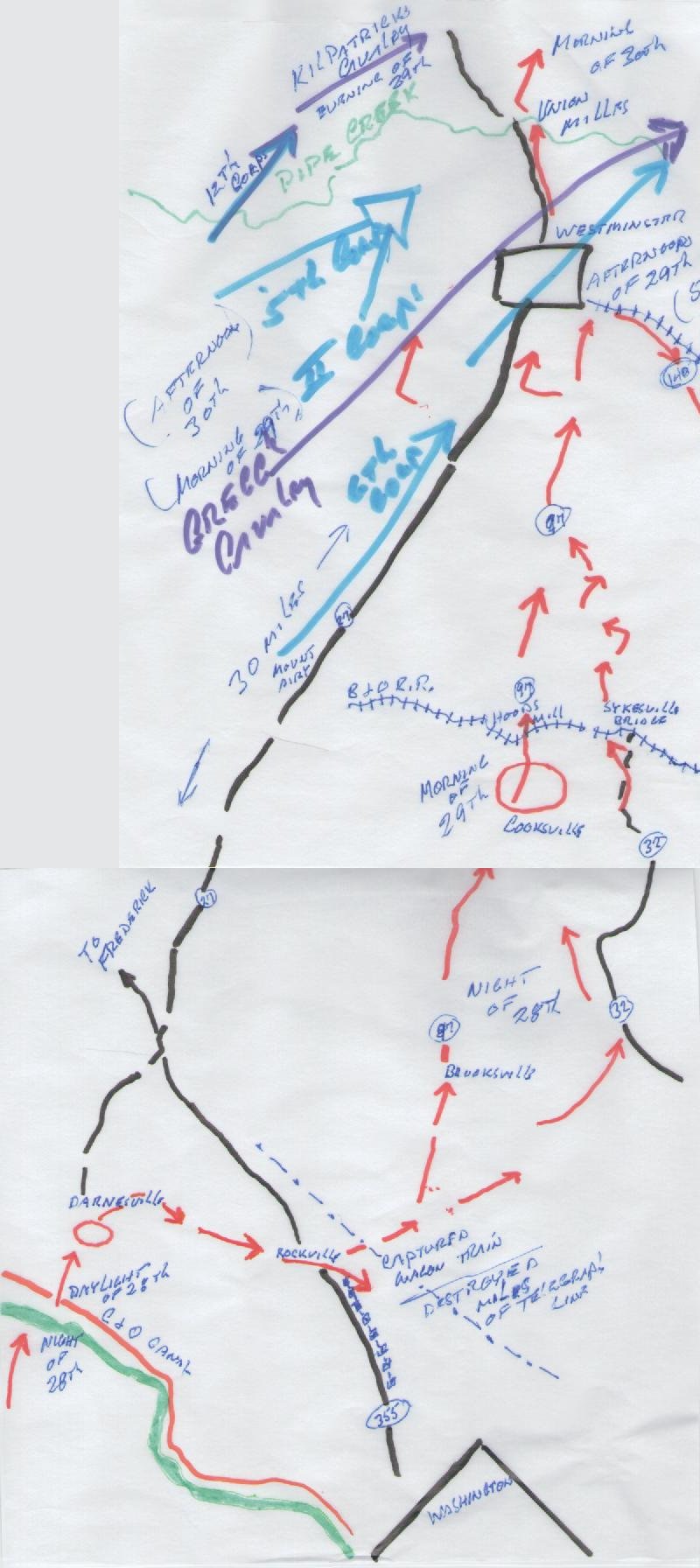

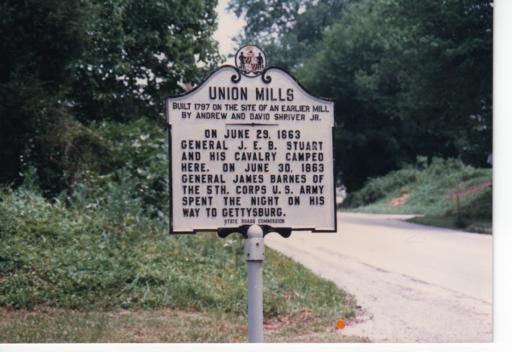

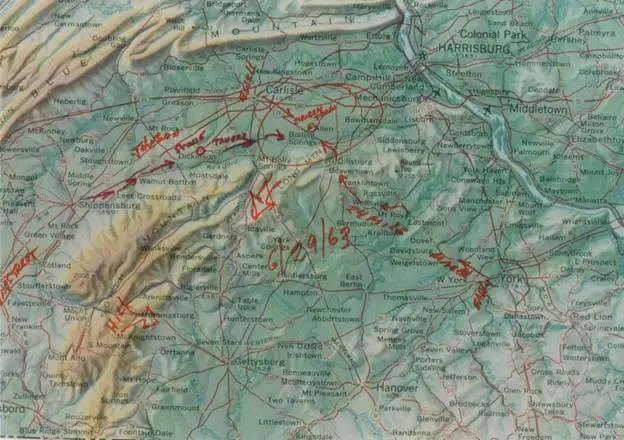

Stuart RidesOn June 21, at Paris in Fauquier County, Stuart had met personally with Lee. In the meeting he submitted his plan of crossing the Potomac in rear of Hooker’s army and moving into Maryland to cut Hooker’s communications with Washington and Baltimore. Lee approved, disclosing that he intended that Ewell send Jubal Early’s division east from Chambersburg, to York, while Ewell moved on toward the Susquehanna River. (See Lee’s and Longstreet’s June 22 letters to Stuart.) As Stuart put it in his report: Lee “notified me that one column (Early’s) should move via Gettysburg and the other (Ewell’s) via Carlisle, toward the Susquehanna, and directed me, after crossing [the Potomac] to proceed with all dispatch to join Early.” Seven days later, the morning of the 29th, Stuart’s cavalry swarmed through Westminister, Maryland, driving a squadron of Delaware’s cavalry from the town. That night, Stuart was at Union Mills, located at Pipe Creek, on the road between Westminister and Littlestown, seven miles away. Camping there, Stuart’s scouts reported that a Union cavalry brigade, commanded by Kilpatrick, had gone into camp at Littlestown. In the early morning hours of the 30th, Kilpatrick passed across Stuart’s front looking for the enemy. Stuart remained stationary at Union Mills until Kilpatrick had passed, taking the road to Hanover, ten miles to the northeast. Stuart then followed Kilpatrick at a distance. About mid-morning on the 30th, while Early’s division was marching west from York, moving through East Berlin and Weiglestown, Kilpatrick, at the head of his column——his rear was moving at the time through the streets of Hanover—came close to the crest of the Pigeon Hills, a string of hills between Hanover and East Berlin. Suddenly, Kilpatrick heard the Bahloom of cannon, realized his rear was under attack from Stuart and turned his column around. Had Kilpatrick continued north to the rim of the Pigeon Hills bluffs he would have seen Early’s column marching west and would have known instantly that the Rebels were moving to concentrate somewhere. He could have harried the march greatly at that point. Instead he spent the rest of the day skirmishing fruitlessly with Stuart.

Why Did Lee Lie?Lee lied in his public reports, because Confederate government politics required it. Trial lawyers, who expect to win their cases by attacking the credibility of their adversaries’ chief witness, show the jury the contradiction between what the witness has said in private and what he has said in public. In Lee’s case, it is clear that, in writing privately to President Davis, on June 23 and 25, he told the plain truth about what he intended doing: He meant to march into Pennsylvania, abandoning his communications with Virginia, and draw the advance of the Union army to a location where he might fall upon it with overwhelming force, cause it to retreat and then, by July 4th, have maneuvered the enemy into the forts in front of Washington. What Lee Said to Davis in Private At the same time General Lee apparently sent his last message to Stuart, June 23, telling him to do the enemy “all the damage you can,” he wrote President Davis this—“Reports of movements of the enemy east of the Blue Ridge cause me to believe that he is preparing to cross the Potomac. . . General Ewell’s corps is in motion toward the Susquehanna. Hill is moving toward the Potomac. . . Longstreet will follow tomorrow.” On June 25, Lee wrote Davis from the right bank of the Potomac as Longstreet’s corps was crossing: “I have not sufficient troops to maintain my communications, and therefore have to abandon them. I think I can. . . embarrass [the enemy’s] plan of campaign in a measure, if I can do nothing more and have to return.” Several hours later, from the left bank of the river, Lee wrote Davis again: “It seems to me that we cannot afford to keep our troops awaiting possible movements of the enemy, but that our true policy is, as far as we can, to employ our own forces as to give occupation to his at points of our selection . . . It should never be forgotten that our concentration at any point compels that of the enemy. . . “ Can any reasonable person not understand what General Lee is saying here? As the battle of Gettysburg was ending, on July 4th, General Lee wrote this privately to President Davis—a blunt statement of the truth of the matter. “After the rear of the army crossed the Potomac, Ewell pushed on to Carlisle and York, passing through Chambersburg. The other two corps closed up on the latter place, and soon afterward intelligence was received that the army of Hooker was advancing. Our whole force was directed to concentrate at Gettysburg. . . “ A more straightforward statement of what Lee did can not be imaged than this. Three weeks later, however, Lee was forced by politics to explain why he had ordered Ewell to send Early to York and Wrightsville; the politicians by this time aware what Lee’s defeat at Gettysburg meant for their country, demanding to know why Lee had objectively taken the tactical offensive when Confederate government policy was to engage the enemy in battle only on the defensive; it being plain to all that Early’s presence at York seemed obviously intended to precipitate an advance by Lee in the direction of Washington. General Lee’s First Public Report On July 31, 1863, in his first report directed to the Confederate Adjutant General, Samuel Cooper, Lee wrote this:

Lee’s first report contains two distinct, but contradictory, themes. In the first paragraph, Lee states the obvious truth that the enemy would naturally conform its movement to the movement of Lee. Thus, the movement of Early’s division to York and Wrightsville and the presence of Stuart between Rockville and Westminister, would induce the Union army’s movement toward Hanover and Manchester, since it telegraphed a probable concentration point of the Confederates at York. In the second quoted paragraph, Lee then shifted gears to manufacture a different reason entirely for Early being sent to York—a reason that Lee had privately disavowed in his letters to President Davis. Despite what he wrote to Davis, Lee claimed that not only did he receive no “report” that Hooker had crossed the Potomac but also that “the absence of the cavalry” left him completely in the dark as to the fact of Hooker’s crossing. This fact, Lee says, induced him to order Early to York, in order to “retain the enemy on the east side of the mountains,” something the movement would clearly do. There is substantial evidence in the record that by June 28th Lee had good reason to think Hooker was across the Potomac, however. First, up to June 23, Lee had received information on a daily basis which documented the fact that Hooker was moving his corps from the Manassas Plain and the Bull Run Mountains towards Leesburg and Edward’s Ferry. Lee made it clear in his letter to Davis that he expected Hooker to cross at any moment. Furthermore, during this time, Elijah White’s cavalry battalion had been roaming through Loudoun County, even at one point crossing the Potomac and destroying a Baltimore & Ohio train at Point of Rocks, just a few miles north of Edward’s Ferry. It seems probable, therefore, that Lee was being informed by White of Hooker’s movements, up to the point White was ordered to join Ewell’s advance where he eventually wound up going with Early to York. Lee let White go, one would presume, only after he didn’t need him any more. Lee also had available as scouts on the Potomac, the Confederate cavalry brigades commanded by Grumble Jones and Beverly Robertson. It is plainly obvious then that “the cavalry” was in fact available to Lee during his movement northward from the Potomac. In the third quoted paragraph, Lee introduces Harrisburg as if it were his objective point. In other words, on June 28th, with Early at York and Hill’s and Longstreet’s corps between Chambersburg and Cashtown, Lee actually intended that his army march north to Harrisburg. It would have taken Early, Longstreet, and Hill two days to arrive together in front of Harrisburg. What then? If Early could not prevent the destruction of the Wrightsville bridge, how could a reasonable person in Lee’s shoes expect to prevent the destruction of the Harrisburg bridges? Once concentrated in front of Harrisburg, with the bridges destroyed, what was Lee to do with his army next? In a trial court, Lee would be laughed off the witness stand, if he tried to sell this story. General Lee’s Second Public Report Despite having written a five page report in July, six months later, in January 1864, Lee files a thirteen page report. From a trial lawyer’s point of view, this hardly makes any sense. Lee’s July report certainly covered the ground. Writing a second report, going over the same matter, creates the reasonable suspicion that the first report was deemed by the government to be insufficient for its propaganda purposes. Something more the government required Lee to say that he had not adequately said.

Lee’s choice of language (or that of his staff which he signed off on) conforms fairly squarely with the language of his June 23 message to Stuart, a message we can accept as authentic only if we believe the document as it has come down to us, is in fact something that was sent to Stuart. The language, in itself, constitutes no indictment of Stuart’s actions, as it includes both the element of “losing no time” getting on Ewell’s right and the element of “doing all the damage to the enemy you can.”

This can hardly be Lee’s words though he signed off on them. “It was expected that as soon as the Federal Army should cross the Potomac” Stuart would give Lee notice? How did Lee expect Stuart to do this, given the fact that he knew Stuart was moving through the enemy corps to their rear. White certainly was in position to give Lee notice; so too were the brigades of Jones and Robertson. But not Stuart. The suggestion that as late of June 28th, Lee would “infer” that Hooker had not crossed, because Stuart had not communicated the fact, seems ridiculous under the circumstances. As early as June 23, Lee knew the enemy had placed a pontoon bridge into position at Edward’s Ferry, that the Union corps were on the march for Leesburg, and that his movement across the Potomac would naturally induce Hooker to cross. Given these undisputed facts, a reasonable person in Lee’s shoes could hardly assume, by lack of communication with Stuart, that Hooker was still in Virginia. Furthermore, the evidence shows that, by the 28th, Lee had “eyes” in position at Fairfield, in observation of the Union force inching into Emmittsburg and beyond, and that he certainly had with him enough cavalry to watch the Middletown Valley from the heights of South Mountain. At this point in his second narrative, Lee changes the reason why Early marched to York. In the first report, the reason was merely to induce Hooker, once he did cross the Potomac, to remain east of the mountains; now the reason Early marched to York became the precursor to Lee’s “advance to Harrisburg.” Lee meant to advance to a location anywhere than Gettysburg, his government wants its public to think.

How the “scholars” could have accepted this statement for a hundred and fifty years as an accurate reflection of reality escapes my intelligence completely. So Early seized the bridge, what next? We are supposed to believe that Lee would place one of his infantry divisions on the left bank of the Susquehanna and order it to march alone through 30 miles of Lancaster County and up to the city limits of Harrisburg, as Lee, with the rest of the army, arrives on the right bank of the river in front of Harrisburg? What reasonable person can doubt that, by the time Lee and Early arrived in front of Harrisburg, the Harrisburg bridges would have been destroyed? What then was Early to do? March back to Columbia, and recross the river on the Wrightsville bridge? Neither Lee nor Early were going to ford the Susquehanna River, at the end of June 1863, that’s certain. The historic water levels of the river emphatically tell us that. If any thing more is required to drive the point home, one need only look at Early’s time table which he sent to H.B. McClellan after the war. Early produced the time table to show that it was never contemplated by Lee that he cross the river at Wrightsville. In his report, Lee admits that Ewell gave Early orders to march to York because he told Ewell to do so. Early’s time table shows that, when he began his march from Chambersburg, on June 25, he left with the understanding from Ewell that on or about June 29th Lee expected Early to be marching west toward Ewell who would be marching east to meet him at or near Churchtown on the road between Carlisle and York. Once the scholars give up the ghost of Harrisburg, the whole house of cards that the battle of Gettysburg happened by accident falls.

The Westminister Church and Graveyard

Where Stuart’s Trooper,

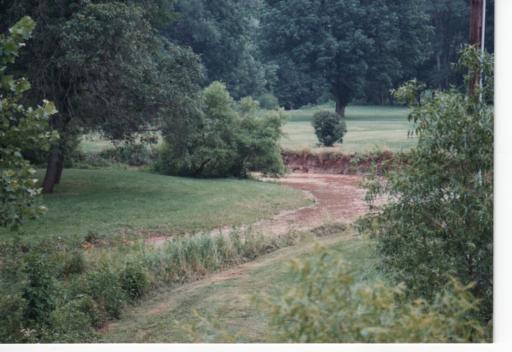

Stuart’s View Northeastward from the Shiver farm at Union Mills, toward Hanover

The Stream of Pipe CreekPipe Creek extends from about Emmitsburg, near the Maryland line, to Union Mills and beyond. When George Meade took Hooker’s place, on the 28th, he ordered three of the Union army corps to move northeast in the direction of York and Manchester, with Reynolds, Howard, and Sickles’s corps standing on Pipe Creek between Emmitsburg and Taneytown.

The street in Hanover where Stuart struck Kilpatrick

Late on the 30th, as Early was marching west, in the direction of Heidlersburg, on the road leading to Arendtsville and Shippensburg, Stuart broke off the engagement with Kilpatrick and moved, with a wagon train he had captured, to the northeast. At Jefferson, he moved north to York, passed by the town and headed straight up the road leading to Dover, Dillsburg, and Churchtown. He arrived at Carlisle on July 1 as the battle was raging between A.P. Hill and John Reynolds’s First Corps at Gettysburg. It is undisputed that JEB Stuart, in riding around Hooker’s army, had not put himself in direct communication with Early, although the circumstances suggest strongly that he was actually aware of Early’s location on the 30th and had attacked Kilpatrick to prevent him from harassing Early’s westward march. Nor is the evidence disputed that Stuart did not inform General Lee that Hooker’s army had actually crossed the Potomac, at Edwards Ferry on the 26th and 27th, headed for Frederick to take a position in front of Turner’s Gap in the South Mountain: a position, Lee’s 1864 report states, so threatened his communications with Hagerstown and Williamsport that he was compelled to concentrate his army east of the mountains. Thus, Lee, the scholars and civil war writers have intoned for generations, was deprived of “his eyes and ears.” Thus, not knowing where the enemy was, he was forced to grope blindly toward Gettysburg and was drawn into a disastrous battle he did not mean to bring on. But this is pure myth that an objective examination of the evidence easily dispels.

Meade Takes CommandAt 1 o’clock, on June 27th, Joe Hooker tendered his resignation to Lincoln. Before daybreak on the 28th, Meade received a courier who brought a message from Henry Halleck, Lincoln’s general-in-chief, that he was now in command of the Union army. Halleck’s message included Lincoln’s order that Meade maneuver the army in such a manner that he cover Baltimore and Washington, it being now known that the Rebel army had appeared at two points along the Susquehanna: force had appeared in front of Harrisburg and at Wrightsville, a town located twelve miles east of York. From this it was assumed that the enemy meant to move on either Harrisburg or Baltimore. In reply to Halleck, Meade sent this message: “I must move toward the Susquehanna, keeping Washington and Baltimore covered and if the enemy turns toward Baltimore to give him battle.” In the execution of this plan, Meade ordered the First and Eleventh Corps to take position in the vicinity of Emmitsburg, the Third and Twelfth Corps to Taneytown, the Fifth Corps to Union Mills, the Second Corps to Union Bridge, and the Sixth Corps to Manchester. By late on the 28th, the Union army was dispersed behind Pipe Creek, manning a defensive line that extended almost thirty miles from one end to the other. Here, for forty-eight hours, Meade waited for Lee’s army to appear against one or the other of his flanks. Meade Waits For Lee Two Days At Pipe Creek

General Lee’s DesignOn July 1, by showing infantry to Buford, who mistakenly thought he was holding Lee back from Gettysburg, Lee was attempting to induce Meade to send forward his infantry to meet him in the rolling countryside between Cashtown and Gettysburg. Lee intended to “fix” the enemy infantry advance close to Marsh Creek, where it crosses the Cashtown road, thus getting the battle away from the grid of streets in Gettysburg that would act as a barricade in favor of the Union army as his infantry pursued its retreat from the area. Lee meant to fix the enemy with a line facing east, using A.P. Hill’s corps, and then when the two lines were grappling like wrestlers, he would have Ewell’s three divisions come down hard on the Union right flank and rear. The Union infantry then would have to turn their right flank on a line perpendicular to their main battle line, thus creating a “hinge” or salient where the two lines connected at a right angle. Ewell’s mission was to push against the short side of the “L” thus formed and break the hinge. This happened and the Union advance was thrown into retreat. But Ewell’s offensive power waned as everyone poured through the streets of Gettysburg. Their formations were broken up in the streets, and Doubleday (he claims) was able to hold the retreat to Cemetery Hill. Had Edward Johnson’s division, of Ewell’s corps, been in the proper place at the proper time the Union retreat would have had no chance to form a defensive perimeter on the hill, and the pursuit toward Pipe Creek would have begun and the “Battle of Gettysburg” would have been over on the first day. But, at the crucial moment, as the Union battle line was collapsing and Reynolds’s and Howard’s troops were fleeing through the streets of Gettysburg, to reach the heights of Cemetery Hill, Johnson’s division failed to materialize at its expected place before night fell, and the battle of the day ended. Was Lee’s Failure at Gettysburg Stuart’s Fault?The scholars say it was: But for Stuart’s ride around Hooker, he would have given Lee timely notice of Hooker’s movement across the Potomac and Lee would then have been in a position to know. Know what? The scholars can’t coherently say. On June 26th, the day Hooker’s corps were crossing the Potomac near Leesburg, Stuart, with three of his brigades, was ten miles distant at Gum Springs, on the Little River Turnpike between Gainesville and Bull Run. Lee, with Longstreet, was at Hagerstown, moving in the direction of Chambersburg. Early was east of Gettysburg, moving toward York and Ewell was leaving Chambersburg, with Rodes and Johnson, heading north toward the Susquehanna. Had Stuart detached a cavalry company to carry news of Hooker’s crossing the Potomac to Lee, the ride would have had to cover a distance of at least sixty-five miles. (Gum Springs to Berryville to Williamsport to Hagerstown and beyond) Assuming the ride was not interrupted by the enemy, it would take a cavalry company, traveling an average of four miles an hour, at least sixteen hours to cover the distance involved. In such case, the news would have reached Lee, at the earliest, sometime late in the night of the 26th or in the night morning hours of the 27th . Suppose, then, that at Hagerstown Lee had received a courier from Stuart; What then? What was Lee supposed to do with the news? Move Longstreet east to Turner’s Gap, to protect his communications with the Shenandoah Valley. Hardly. The available evidence shows that no courier from Stuart came to Lee after Lee crossed the Potomac on the 25th with Longstreet’s corps. But it does show clearly that Lee already knew enough to know Hooker was crossing the river, and what Lee’s mind-set was, in ordering the army across the Potomac and into Pennslyvania. In a letter written to President Davis, on June 23, Lee wrote this: “Reports of movements of the enemy (obviously “reports” from Stuart) east of the Blue Ridge cause me to believe that he is preparing to cross the Potomac. A pontoon bridge is said to be laid at Edward’s Ferry and his army corps that he had advanced to Leesburg and the foot of the mountains appear to be withdrawing. . . General Ewell’s corps is in motion toward the Susquehanna.” On the same day, in a letter to Imboden, whose cavalry was to move north on Ewell’s left, he ordered a string of couriers to be set up between him and Ewell. On the same day he wrote Stuart, giving him authority to exercise his discretion whether to move north east or west of the Blue Ridge:

From these June 23 letters of Lee’s, it is reasonably clear that Lee knew that Hooker was in the process of crossing his army over the Potomac and would be moving in the direction of Frederick to place his army in front of Turner’s Gap, expecting Lee to march his army through the gap toward Frederick and Washington. (Lee had said as much in earlier June letters to Davis.) Two days later, on June 25, as the first of Hooker’s corps was crossing the Potomac at Leesburg and Longstreet’s was crossing at Williamsport, Lee wrote Davis again, from “opposite Williamsport:” “I have not sufficient troops to maintain my communications, and therefore have to abandon them.” This constitutes a clear admission that Lee had no intention of trying to maintain his communications with the Shenandoah Valley and, thus, had no reason to react to the presence of Hooker’s corps close to Turner’s Gap, by scurrying Longstreet to block Hooker from advancing west into his rear. Hooker’s presence at Frederick, however, certainly was important to know, because it meant Hooker was in proximity to the line Chambersburg—Cashtown—Gettysburg which was Lee’s intended line of operation toward concentration and a general battle. That concentration and a general battle was always the plan in Lee’s mind, the evidence overwhelmingly shows: On June 25th, after Longstreet’s corps was across the Potomac at Williamsport and moving toward Hagerstown, Lee sent Davis a second letter, writing this: “It should never be forgotten that our concentration at any point compels that of the enemy. . . .” A principle repeated by George Meade almost word for words days later, when, on June 30, he wrote to John Reynolds: “If [the enemy] advance against me, I must concentrate at that point where they show the strongest force.” Earlier, on June 8, Lee had written essentially the same thing to James Seddon, the Confederate secretary of War—“[T]here is nothing to be gained by this army remaining quietly on the defensive. . . there is great difficulty and hazard in taking the aggressive with so large an army in [(my) front. Unless it can be drawn out in a position to be assailed, it will take its own time. . . to renew its advance on Richmond. . . I think it is worth a trial to prevent such a catastrophe.” Lee repeated this yet again, in his first June 25 letter to Davis, writing: “It seems to me that we cannot afford to keep our troops awaiting possible movements of the enemy, but that our true policy is, as far as we can, so to employ our own forces as to give occupation to his at points of our own selection.” Certainly that point was not Harrisburg. Lee knew that Hooker would have to conform to his movement which was like that of a fisherman throwing his net across the expanse of country between the mountains and the Susquehanna, with no one on the Union side thinking seriously for a moment that his objective was to actually cross his army over the Susquehanna River, and not thinking for a moment that Lincoln would allow the Union army to move west of South Mountain when the Rebel army was reported moving east of it. The plain facts of nature demonstrate that it was impossible for Lee to cross the Susquehanna. The Susquehanna, at both Wrightsville and Harrisburg, is over a mile wide. It can be crossed only on a single bridge at each location and, as the record shows at Wrightsville, the bridges could be easily destroyed by defenders on the north side. It is simply silly to think Lee really thought for a moment of “capturing” Harrisburg. To the extent Lee’s existing messages to Ewell suggest otherwise, such as “Capture Harrisburg if it comes within your means,” the subject is meant as a diversion in the event the messages were seized by Union forces in their transmission to Ewell. View of the Susquehanna at Harrisburg

The truth of Lee’s mind-set is revealed in a lie. In Lee’s 1864 report, this is written: [Early’s] expedition to York was designed in part to prepare for this undertaking (“move upon Harrisburg”) by breaking up the railroad and seizing the bridge over the Susquehanna at Wrightsville.” Lee’s staff, in writing this, no doubt was hanging the statement on what Jubal Early had written, in his report dated August 22, 1863: “I directed Gordon to march to [Wrightsville] bridge and secure it at both ends, if possible.” How silly is this? In the real world, when Early rode to Wrightsville on the 28th, he found the wooden structure of the bridge aflame, Union militia having set it afire. The fire destroyed the bridge and almost burned down the whole town. Surely Lee knew, when he crossed the Potomac, that he had no reasonable chance of actually crossing the Susquehanna, much less “capturing” Harrisburg, the city and bridgehead being defended by Couch’s troops. In his August 1863 battle report, as well as in his autobiography, published after his death, Jubal Early admitted the truth of the matter: “In accordance with instructions received from General Lee, Ewell ordered me to move across South Mountain and through Gettysburg to York, for the purpose of cutting the North Central Railroad and destroying the bridge at Wrightsville.” The Wrightsville Bridge

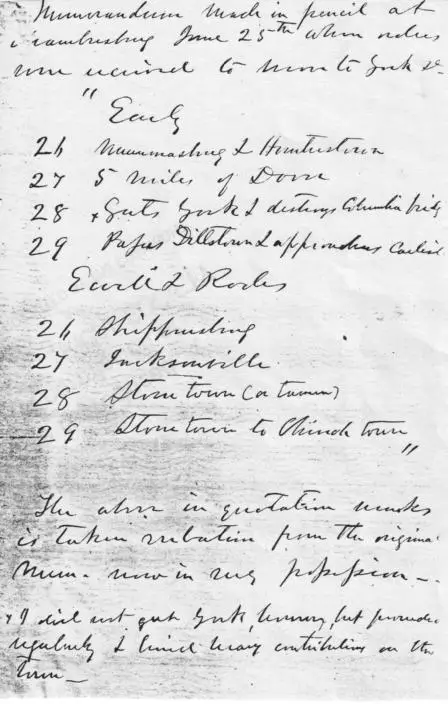

Earlier, in 1878, writing privately to H.B. McClellan (cousin of George), one of Stuart’s staff officers who had sent Early his manuscript, Life and Campaigns of JEB Stuart, Early revealed what Lee actually intended by moving Ewell toward the Susquehanna. On June 25, as Lee and Longstreet were crossing the Potomac at Williamsport and Lee was writing to Davis, Early met with Ewell at Chambersburg. Ewell had received orders from Lee, and informed Early where Lee expected him and Early to be for the next four days (the 25th to the 29th). Ewell had drawn up a timetable and Early made a copy. Early reproduced the timetable in his letter to McClellan.

The Timetable

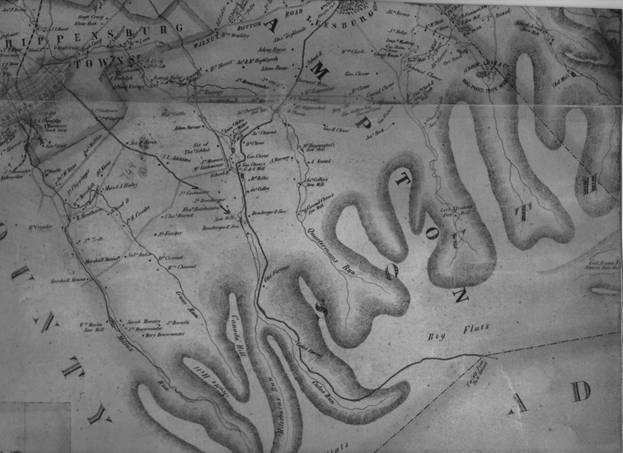

The timetable reveals two important facts that show Lee’s intent to fall on the enemy at Gettysburg. First, the table shows that, on the 28th, Early was to “gut York and destroy” the Wrightsville bridge. Second, that, on the 29th, Early was to move northwest on the Dover/Dillsburg Road and approach Carlisle. On the 29th, at the same time Early was marching, Ewell was to move from Stone Tavern to Churchtown. Churchtown was situated behind Long Mountain, a northern spur of South Mountain. At that location, Ewell would be “west of the mountains” and in position to move directly south toward Gettysburg or Cashtown, when called upon by Lee to do so. (Early’s letter to McClellan is in the possession of the Virginia Historical Society.) Ewell’s and Early’s Planned Concentration Point for the 29th

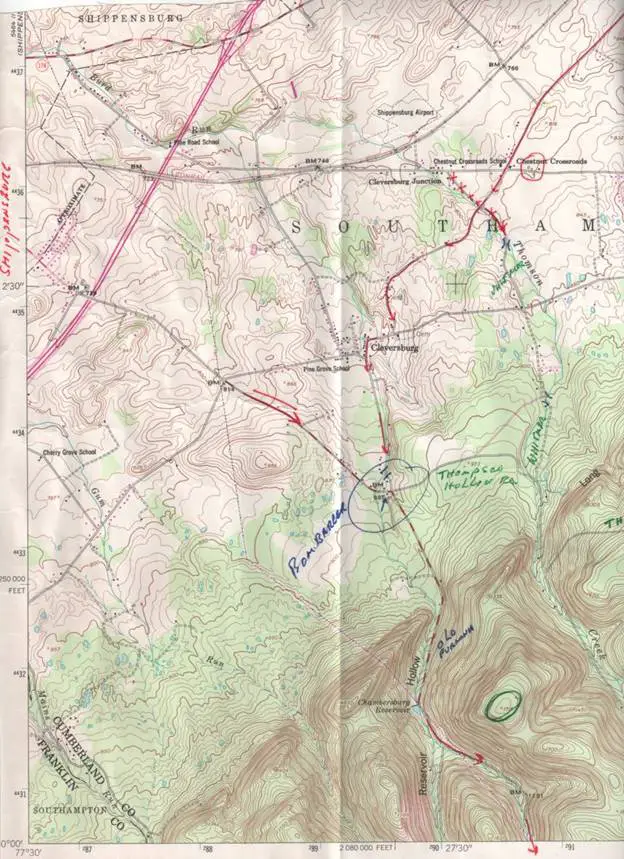

But, for a reason the record does not explain, Early did not conform to the timetable on the 29th. On that day—the day he was supposed to be marching west—he remained camped at York. He claims he was delayed by the failure of his cavalry—French’s 17th Virginia and White’s battalion—to timely burn all the railroad bridges between Hanover, York and the line of the North Central as it passed Wrightsville on its way to Baltimore. The more likely explanation, though, is that he received a message from Lee (through Ewell) to hold his position another day. Early acknowledged receiving two dispatches from Ewell while he was at York: The first was “a handwritten note” dated June 28 at 2:00 p.m. When it was received, Early does not exactly say, but, assuming it existed and was in fact so timed, the courier could not have arrived at York before about midnight on the 28th; the distance between Carlisle and York being about 40 miles. In his message, Early says Ewell wrote, “General Lee has a heavy force (`tight corps’) toward Gettysburg. General Lee seems inclined to concentrate about Chambersburg so I don’t know yet whether I move toward Harrisburg or not.” (This could have been code for “Don’t move yet.”) In accordance with these instructions, Early told McClellan, he put his “whole command in motion at daylight on the 30th, taking the route by way of Weiglestown and East Berlin toward Heidlersburg, so as to be able to move from that point to Shippensburg or Greenwood by way of Aaronsburg, as circumstances might require.” (Weiglestown is on the road to Carlisle. East Berlin is on the road to Heidlersburg and Arendtsville.) As Early reached East Berlin, he heard the guns booming between Kilpatrick and Stuart at Hanover, ten miles to the south. Here, a courier appeared from Ewell with a dispatch that said Ewell was then moving with Rodes by way of Petersburg to Heidlersburg and directed Early to march to the same place—the place Early was marching toward. (With the enemy’s left wing now showing force at Emmitsburg, Lee has decided to change Ewell’s concentration point closer to Gettysburg, from Churchtown to Heidlersburg.) The Failure of Johnson’s Division to Arrive in Time at GettysburgThe road from Shippensburg to Arendtsville was crucial to Lee’s effort to overwhelm Meade’s advance of two corps at Gettysburg. If a “sketch” of a message Lee supposedly sent to Ewell, the morning of the 28th, is in fact accurate and not a fabrication, which is questionable, Ewell learned from Lee sometime on the 28th that he wanted Ewell to move south on the ”east side of the mountains” in the direction of Heidlersburg and join his “other divisions” to Early’s. Lee’s reconstructed message (by Charles Venable) also stated to Ewell that “if the roads which your troops take” are good, your wagon trains “had better follow” them. (Venable’s “sketch” is in the possession of the Virginia Historical Society.) Yet, for some reason the evidence does not show, Ewell ordered Johnson to move his division, with the entire trains of the corps, south and cut into the Cashtown Gap road, Longstreet’s corps was using, to reach Gettysburg. On this point, Ewell, in his report of his operations, stated merely: “On the night of the 30th Rodes was at Heidlersburg. Early 3 miles off, on the road to Berlin. Johnson was between Green Village and Scotland.” Johnson, in his report, was more precise, writing: “On June 29th, in obedience to orders, I countermarched (from within three miles of Carlisle) to Green Village, thence to Scotland, to Gettysburg, not arriving in time, however, to participate in the action. The march was 25 miles, rendered difficult by the obstructions of Longstreet.” Lee’s plan to crush the Union advance at Gettysburg failed, not because of Stuart’s ride around Hooker, but because Ewell did not bring Johnson’s division with him to Heidlersburg. Even if Ewell’s excuse is that he had previously received an order from Lee to march toward Chambersburg and that Johnson was already in motion toward that point when he received the contrary order to move south east of the mountains, he could have ordered Johnson to turn onto the Arendstville road at Shippensburg and cross the South Mountain to join him at Heidlersburg. 1858 Cumberland County Road Map showing the road Johnson could have taken between Shippensburg and Arendtsville

Current Day Quadrant Map showing the road Johnson should have taken to reach Gettysburg on the first day.

Both the 1858 county road map and the current quadrant map show the location of Old Furnace. This is a landmark that still exists, at least as of the late 90s when the road was followed and mapped as shown. The Furnace at that time was seen close to the left shoulder of the road (north side). It is made of stone and rises about 20 feet to form a bee hive, much in appearance as Kathryn’s Furnace at Chancellorsville. Small growth trees were growing out of the top and it was covered with brush and grass. The bottom, at the throat used to insert logs for charcoal, was to some extent collapsed. Presumably someone is making an effort to preserve this important landmark for future generations to enjoy. Ewell’s unfathomable decision to order Johnson’s entire division to countermarch toward Chambersburg from the vicinity of Carlisle, resulted in the failure of his corps to pursue the fleeing Union forces onto Cemetery Hill and drive them on down the roads toward the Mason-Dixon line. The decision must have been based on his concern for his trains, but to ignore Lee’s instruction that he had better keep his troops to the east side of the mountains was gross stupidity. Even if his concerns for his trains were not unfounded, he had no intelligent excuse for not taking most of Johnson’s division with him, having it follow Rodes toward Heidlersburg to join Early and move on Gettysburg. Certainly, had Jackson commanded the corps all three divisions would have appeared north of Gettysburg, and probably the trains would have been in the rear. Johnson could have been sent across the mountains on the road between Shippensburg and Arendstville. As you climb out of the Cumberland Valley and go around the first mountain shown on the quadrant map, you are climbing a steep hill on a road, in 1863, that would have been earth, perhaps with gravel. The evidence shows that on the day of concentration it was raining on the west side of the South Mountain. How much rain fell cannot be said with precision, but it is possible the roads might be muddy and the wagon trains possibly mired at points. Once you reach the Adams County line, you are on Flat Mountain, a tabletop which extends to the east side of South Mountain. As you come down the east slope, you must pass through “The Narrows,” a narrow defile with a stream cutting alongside and you come out in front of Arendtsville. Gettysburg is straight-ahead eight miles over rolling countryside. It is possible that Union forces, civilian or military, might have felled timber along the road from the Old Furnace to the Narrows, and that the Narrows exit might have been blocked by barricades. The distance between Old Furnace and the Narrows is a good five miles. But Johnson’s infantry could have easily brushed the obstacles out of the way and marched on, his trains passing on toward Chambersburg, if necessary, where they would have been held until Longstreet’s infantry passed the Cashtown Gap. Some fear, some weakness of military character, paralyzed Ewell’s will to be audacious. The existing evidence, when complied in its entirety, plainly shows that General Lee planned the happening of the Battle of Gettysburg almost from the day the Battle of the Antietam ended, in September 1862, sending Stuart on a scout of the Cashtown Gap and the countryside around Gettysburg. In the winter and spring of 1863, General Lee organized his army for the campaign and he prepared the civilian leaders for the movement, making it plain to them that its purpose was to strike the enemy a blow which would destroy their ability to mount a campaign against Richmond in 1863. Plans, though, are good only to the point the battle begins and that rule operated at Gettysburg, with Ewell’s failure to join Johnson’s division to Rodes’s on the move to Heidlersburg: Meade repulsed Lee at Gettysburg because Hooker killed Jackson at Chancellorsville. Such is the glorious uncertainty—the fortune—of war. Joe Ryan | ||||||||||

|

BOOKS AVAILABLE TO READ John Mobsy, Stuart’s Cavalry in the Gettysburg Campaign (Moffat, Yasrd 1908) H.B. McClellan, The Life and Campaigns of Major-General J.E.B. Stuart (Houghton & Mifflin 1885) Encounter at Hanover: Preludge to Gettysburg (Hanover Chamber of Commerce 1963) Warren C. Robinson, Jeb Stuart and the Confederate Defeat at Gettysburg University of Nebraska Press 2007) Eric J. Wittenberg & David Petruzzi, Plenty of Blame to Go Around: Jeb Stuart’s Controversial Ride to Gettysburg (Savas Beatie 2006) Mark Nesbitt, J.E.B. Stuart and the Gettysburg Controversy Stackpole Books 1994) |

|

Joe Ryan Original Works @ AmericanCivilWar.com |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

About the author: Joe Ryan is a Los Angeles trial lawyer who has traveled the route of the Army of Northern Virginia, from Richmond to Gettysburg several times. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Battle of Gettysburg

General Robert E. Lee

General JEB Stuart

General Jubal Early

Confederate Commanders

General Joseph Hooker

Union Generals

American Civil War Exhibits

State Battle Maps

Civil War Timeline

Women in the Civil War