| Read all Joe Ryan Original Works | Comments and Questions to the Author |

General Grant And The Vicksburg Campaign

April 6, 1862 to July 4, 1863

We have seen how Grant skyrocketed into the rank of major-general, by his seizing the initiative, moving his force from Fort Henry, on the Tennessee River, to Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River and gaining the surrender of the Confederate garrison there. His major-general's rank made him second in seniority to Henry Halleck, commanding all forces in the West, and put him in command of the build-up of Halleck's forces at Pittsburg Landing. Grant used this opportunity to invite Sidney Johnston to attack the troops in the staging area which Johnston did. (Johnston had no choice.) As a result, the Union forces on the west bank of the Tennessee River were driven two miles from their camps to the edge of the river, at which point the army of Don Carlos Buell arrived and pushed the Confederates back to Shiloh Church.

Grant's next performance came about seven months later, when he sent an infantry force, under Sherman's command, by steamers down the Mississippi River to Chickasaw Bayou, just north of Vicksburg, to make a land assault against the Vicksburg defenses. As Sherman moved by water, Grant began marching an infantry force from Holly Springs, Mississippi, toward Vicksburg, 202 miles away. He got only a few miles, as far as Oxford, Mississippi, and was forced by circumstance to call the campaign off and turn back to regain his base of supply. Grant had left a single brigade at Holly Springs to guard the millions of dollars worth of supplies that he had built up there, and the Confederate general, Van Dorn, taking a page from General Lee's book, swept into the place with 3,000 cavalrymen, pushed the infantry brigade aside, and, like Jackson at Manassas Junction, burned the place and everything in it to the ground. (Only Grant knows what he thought he was doing at the time.)

Sherman, in his memoirs, writes about this, in a way that is laughable.

"Grant has told me since the war, he would have gone on from Oxford and would not have turned back because of the destruction of his depot at Holly Springs. The distance from Oxford to rear of Vicksburg is little greater than by the route we afterward followed, from Grand Gulf to Jackson, during which we had neither depot nor train of supplies."

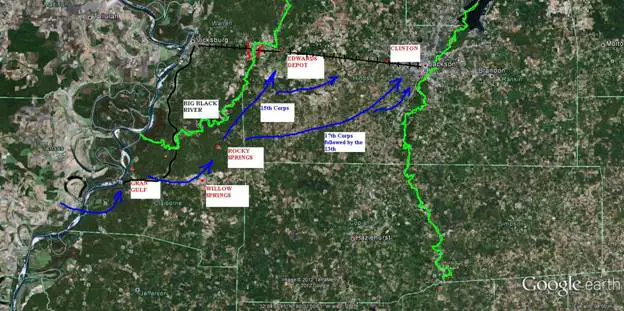

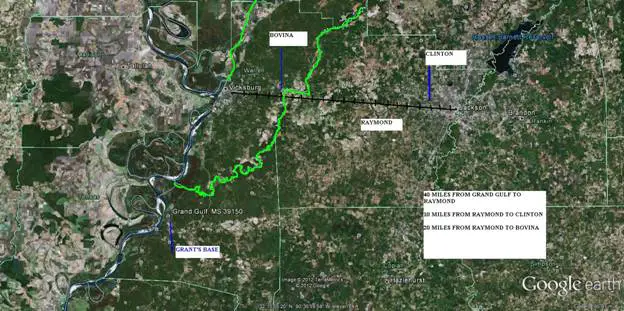

Sherman is lying. During the first week of May 1863, using steamboats and gunboats, Grant crossed three corps—six divisions totaling sixty thousand men—over the Mississippi River, from its west bank to its east bank, pushed a Confederate brigade occupying Port Gibson out of the way, and took possession of Grand Gulf, making it his base of operations against Vicksburg. McClernand's and McPherson's corps―by now Grant had dumped two of his three Illinois cohorts, leaving Hurlbut at Memphis, and Prentiss, at Helena, Arkansas—then he marched 45 miles to the village of Raymond where the single road through the region splits, the left hand branch leading to Clinton, the right hand branch directly to Jackson through Mississippi Springs.

Grand Gulf to Jackson

As Sherman tells the story, on May 7, he got two of his three divisions across the river at Grand Gulf and marched 18 miles to Hankinson Ferry on the Big Black (a spot several miles west of Raymond).

A build up of supplies quickly commenced at Grand Gulf and wagon trains began moving up the road, following Grant's army. Seven days later, having covered a grand total of 65 miles, Sherman's and McPherson's corps arrived at Jackson, while McClernand arrived at Edward's Depot, a point on the Vicksburg-Jackson Railroad, a few miles east of the railroad bridge crossing of the Big Black River. (A month later, on June 10, 1863, General Lee began moving 80,000 men, organized into three corps of three divisions each, 120 miles, from the Rappahannock River at Chancellorsville to Gettysburg, cutting loose from his communications with Virginia in the process. for a period of six weeks.)

Contrary to the situation General Lee encountered at Gettysburg―meeting the Army of the Potomac, about 100,000 strong—Grant's corps when they reached Jackson found an empty town.

The sole Confederate force available to oppose Grant's movement to Jackson was the 23,000 men of Pemberton's army which had moved east from Vicksburg as far as the railroad bridge at the Big Black River and then had turned southeast, marching a few miles with the supposed plan of "cutting Grant's communications," But, Pemberton, quite aware of Grant's overwhelming force of manpower, quickly made an about face and took a defensive position in front of the Big Black bridge, facing McClernand's corps at Edward's depot.

Pemberton's Defensive Perimeter at the Big Black

Once, again, as at Shiloh, the record shows undisputedly the fact that, from the beginning of the war to its dismal end, the Lincoln Government had the overwhelming advantage of a bottomless well of manpower to draw upon. Indeed, if one takes the time to examine the record, it is plan that Lincoln's Illinois crowd had carefully analyzed the strategic situation the war would create, before the war began, and actively orchestrated events so that Illinoisans would command military affairs in the West and, using the manpower of the Western States, eat the Confederacy up, from its back end to its front. The Davis Government, in consequence of this pathetic overmatch, had no reasonable chance, from the moment Lincoln successfully instigated the war, to hold on to the territory comprising the States of Kentucky, Missouri, Arkansas, Western Tennessee, Louisiana, and the upper sections of Mississippi and Alabama. This was proven at Shiloh and it was proven again at Vicksburg, Little Rock and Port Hudson. The Confederacy simply never had the manpower available to hold its own simultaneously in the three distinct sectors of the war: Mississippi―Middle Tennessee—Virginia. If the Confederacy were to support General Lee's army in Virginia, giving it the strength to conduct offensive operations against the Army of the Potomac, all it could do in Middle Tennessee was stand on the defensive and it could do that only at the expense of the defensive force holding Vicksburg in Mississippi.

General Joseph Johnston tells the story. Appointed by President Davis to the command of the Department of the West, encompassing Tennessee and Mississippi, Johnston met with Davis at Chattanooga, in January 1863, and discussed the problem of manpower vs. space. Davis left Chattanooga and went to Murfreesboro to confer with Bragg who was facing Rosecrans's army at Nashville. Bragg agreed to send Stevenson's division to Pemberton at Vicksburg. Davis and Johnston, together, then went to Vicksburg and inspected the fortifications and conferred with Pemberton.

"In conversing with the President in relation to the defense of Vicksburg, Pemberton and myself differed widely as to the mode of warfare best adapted to our circumstances. I told Davis that two armies far apart (Bragg's and Pemberton's), having different objectives, and opposed to adversaries having different objectives, could not be commanded by a single general. Davis said he thought it necessary to have an officer with authority to transfer troops from one army to the other in an emergency.

I certainly was not the proper selection; for I had already expressed the opinion distinctly that such transfers were impracticable, because each of the two armies was greatly inferior to its antagonist; and they were too far apart from each other for such mutual dependence."

Johnston, in his memoirs, claims that there were 55,000 men in Arkansas, under the command of Holmes, which could have crossed the Mississippi and joined with Pemberton, thus solving the problem of being overmatched by the forces under Grant's command. The record, however, does not support Johnston's belief. On July 4, 1863, at the same time Pemberton was surrendering Vicksburg, Kirby Smith, with 7,000 men, attacked Helena, Arkansas, 175 miles north of Vicksburg. Helena was defended by Prentiss, with 4,000 men. Prentiss had previously commanded 20,000 men at Helena, but Grant took 16,000 of them with him to Vicksburg. Helena was used as the base to capture Little Rock two months later. There were no more organized Confederate forces in Arkansas, closer to Vicksburg than this.

President Davis, in his memoirs, makes an argument to rebut Johnston's theme that Vicksburg was indefensible, unless substantially reinforced, a reinforcement that Davis could not allow, if Bragg was to hold his tenuous position in Tennessee. On May 9, 1863, as Grant's horde was marching up the left bank of the Big Black River toward the line of the Vicksburg-Jackson railroad, Davis ordered Johnston, who was then very sick and at Tullahoma, Tennessee, to go to Jackson and "take chief command of the forces." Davis told Johnston he could take 3,000 troops with him. Johnston arrived at Jackson, Mississippi, on May 13, just after Sherman's and McPherson's corps stepped onto the Vicksburg-Jackson Railroad at Clinton. Johnston had with him at Jackson, less than 8,000 men. Johnston sent messages to Pemberton, asking him to march east and attack the enemy force in front of Jackson. Pemberton sent a message back, "I moved with whole available force, about 16,000."

Pemberton arrived at Edward's Depot, a short distance east of the Big Black railroad bridge and held a council of war. Should he go on as Johnston wished, to strike Sherman and McPherson, or should he move south, and make a try of cutting Grant's communications with Grand Gulf? The majority of the generals attending voted to strike at Sherman and McPherson. Pemberton ordered his force to march south. The march lasted but a few miles when Pemberton decided it would be better that he maintained the defensive position at the Big Black Bridge.

Here, Davis, in his memoirs, makes a reasonable point. In his first effort at marching to Vicksburg, Grant had been induced to turn back when he lost his communications with his base at Holly Springs. This result had been achieved by Van Dorn's cavalry force. Afterwards, however, Johnston had ordered Van Dorn to move to Tennessee and guard the territory south and southeast of Nashville, in order that Bragg's army might take advantage of the supplies that could be culled from the area. Pemberton had asked Johnston, in April, to return Van Dorn's cavalry to him, but Johnston refused, stating: "Van Dorn's cavalry is much more needed in Tennessee than in Mississippi, and cannot be sent back as long as this state of things exists." Citing this situation, Davis writes, "We had lost the opportunity to cut Grant's communications while he was making his long march over the rugged country between Grand Gulf and Vicksburg."

But Davis's suggestion does not stand up to the facts. The country between Grand Gulf and Vicksburg was not "rugged." It was country to be sure, but it was filled with plantations, the resources of which Grant's troops digested like locusts culling a wheat field. And Grant's "march" was not "long." It lasted only a week, from about May 8 to May 16. Grant's troops marched with four days rations, and they were followed pretty quickly by wagon trains carrying supplies. Van Dorn's cavalry certainly could have irritated Grant's progress, but, unlike at Holly Springs, Van Dorn would not have had any chance of destroying Grant's base at Grand Gulf.

President Davis tells us how he dealt with Grant's huge superiority in manpower this way:

"Grant with his large army was now marching into the interior of Mississippi. The country through which he had to pass was for some distance composed of abrupt hills, and all of it poorly provided with roads (true). There was reasonable ground to hope that, with such difficult communications with his base of supply, and the physical obstacles to his progress, he might be advantageously encountered at many points and be finally defeated."

Note: President Davis's statement is ridiculous. Precisely because of the hills and non-existent roads, Pemberton was limited to attempting to cut Grant's communications at or near Raymond, on the single road between Grand Gulf and Jackson. Worse, still, is the idea that Pemberton's 16,000 men could "advantageously encounter" Grant's corps (they were marching in tandem) and defeat them.

What was President Davis's solution to the manpower problem Pemberton and Johnston faced? He could have ordered Bragg immediately on learning Grant was opposite Bruinsburg (just south of Grand Gulf), to send by train (at least a week, if not two, was needed to conduct the transfer) half his army to reinforce Pemberton's and, thus, make it competitive with Grant's. Of course, had Davis done that, he would have had to have stopped Lee in his tracks and ship the same number from Lee's army to Bragg's, if he meant to keep Bragg's grip on middle Tennessee. The poor man, of course, could not do anything of the sort; so what did he do? He tells you in his memoirs.

"In such warfare as was possible, that portion of the population who were exempt or incapable of full service in the army could be very effective as an ancillary force. I therefore wrote to the Governor, Pettus, requesting him to use all practical means to get every man and boy, capable of aiding their country in its need, to turn out, mounted or on foot, with whatever weapons they had, to aid the soldiers in driving Grant from our soil."

Just pathetic. Old men and boys, with a shotgun in their hands, to do what? Take pot shots at the blue horde? Throw themselves under the carriage wheels? These people need to give up.

As at Shiloh, Grant's performance as a field commander at Vicksburg leaves much to be desired. The fiasco of his land march south to Vicksburg aside, his attempts to "charge em" out at Vicksburg were easily brushed aside by Pemberton's little army. First, Grant sent Sherman, with his corps of three divisions, to attack the north face of Vicksburg's bluff by crossing Chickasaw Bayou. Sherman attacked for two days and got nowhere. Next, once Grant got his army up to the east face of Vicksburg, he sent the whole of his force―three corps reinforced with two divisions—against Pemberton's system of detached works, redans, lunnettes, and redoubts, with the usual profile of raised field works, connected with rifle pits, and got exactly nowhere.

Let Sherman tell it.

"My corps moved on and reached the Benton road and gave us command of the peninsula between the Yazoo River and Big Black. At this point Haines Bluff was abandoned. Gunboats and supply ships now steamed up the Yazoo.

Two assaults were made on May 18 and failed by reason of the great strength of the position and the determined fighting of the garrison. We attacked again on May 22, twice, and again we were repulsed. Thereafter our proceedings were all in the nature of a siege. General ("I propose to move upon your works immediately") Grant drew more troops from Memphis, to prolong our line to the left, so as to completely invest the place. Good roads were constructed from our camps to the several landing places on the Yazoo River, to which points our boats brought us ample supplies; so that we were in a splendid position for a siege.

By this time Grant had received J.G. Parkes's 9th corps (two divisions more) which occupied Haines Bluff. And, also, Smith's division arrived. (On June 19, Grant again attacked the Confederate center and left. Repulsed. On June 22, he tried again. Repulsed.)

For six weeks thereafter we dug our way almost right up to the enemy's trenches."

Note: And Lincoln was beside himself, in the spring of 1862, when McClellan did exactly the same amount of digging, without throwing men's lives away on frontal assaults when the open space necessary to cross was too wide.

Grant's Rear Guard Entrenchments, holding his back at Vicksburg

Grant had so many men available to him that he was able to pull four divisions out of the siege line and use it to build fortifications at the Big Black, in his rear, to protect himself from attack by Johnston who had creeped forward after Sherman and McPherson destroyed Jackson. Grant had nothing to fear from Johnston, because Johnston's only plan, given the unavailability of troops to fight with, was to help Pemberton if he tried to break out.

By this time, though, from various sources, Johnston had now about 20,000 men. The idea of using the force to attempt to force a passage of the Big Black against Sherman's four divisions, then meet and defeat the whole of Grant's army while Pemberton came out to fight, too, was not seriously considered by Johnston, or Pemberton. Johnston seriously considered attacking Sherman's position at the Big Black, if Pemberton would use the demonstration to some how break out and get away to the south or north, the two rebel forces uniting at some point east of Jackson.

Johnston states the case well enough.

"I wired Confederate Secretary of War Seddon, `To take from Bragg what is required to deal effectively with Grant will involve yielding Tennessee. It is for the Government to decide.'

Mr. Seddon replied on June 16: `I rely on you to avert the loss. If better resources do not offer, you must attack' (This sounds like Lincoln badgering McClellan, in April 1862.)

I replied on June 19: `You do not appreciate the difficulties in the course you direct, nor the probability and consequence of failure. Grant's position, naturally strong, is entrenched (unlike at Shiloh), and protected by powerful artillery, and the roads obstructed. His reenforcements have been at least equal to my whole force. The Big Black covers him from attack, and would cut off our retreat if defeated. We cannot combine operations with Pemberton, from uncertain and slow communication. The defeat of this little army would at once open Mississippi and Alabama to Grant.'

Seddon replied: `Consequences realized. I take the responsibility, and leave you free to follow the most desperate course the occasion may demand. Rely upon it, the eyes and hopes of the whole Confederacy are upon you, with the full confidence that you will act, and with the sentiment that it is better to fail nobly daring (hog wash), than, through prudence even, to be inactive. I rely upon you to save Vicksburg.'" (Maybe praying to God could have helped.)

On June 28, Joe Johnston ordered his "little army" to move toward the Big Black. In the afternoon of July 1, his three divisions came near the river (Some of these troops came from Bragg, some from Beauregard in Charleston.). He spent two days in reconnaissance, from which the conclusion was reached it was impossible to get anywhere against Sherman's front from the north of the railroad. He turned to consider how to get at Sherman from the south side.

On July 3, Johnston sent Pemberton a message that he would attempt, on the 5th, to attack Sherman, to create a diversion which Pemberton might use to cut his way out. At the same time, Pemberton was meeting Grant between the lines. Like Lee at Appomattox, he came with one aide. Grant brought all his major-generals of which there was a slew. Grant demanded "unconditional surrrender." Pemberton told him to shove it, if he expected to get that, he would have to burn some more lives, and a lot more time. As far as Pemberton was concerned Grant could hammer away until the garrison was starving to death, or he could put the 17,000 soldiers holding the Confederate lines on parole and they would go home. Grant blustered, then he buckled (perhaps waking up to the fact that he just might get pinched), and the rebel soldiers put down their rifles and went home.

The key to the strategic defense of Vicksburg was the Confederates' possession of Haines Bluff. By possessing Haines Bluff, the rebels could have kept Grant at bay forever. Had the Davis Government gotten to Vicksburg, before Grant established his base at Grand Gulf, the 22,000 men that it later pulled from Bragg's army, from Lee's, and from the Charleston garrison, Johnston might have gotten this force behind the Big Black to bolster the defense of Haines Bluff, before Grant got up.

Had, at the same time, all the cavalry possible been rounded up from Tennessee and sent to operate against Grant's communication with Grand Gulf, Grant might well have been forced, yet again, to back up to the Mississippi River where the Union Navy could protect him. As it was, the Government's effort to defend Vicksburg quickly resulted in Rosecrans's army forcing Bragg back to Chattanooga, and the loss of Chattanooga that followed, in September 1863.

Grant took Haines Bluff From the Rear,

by Marching Up The Left Bank of the Big Black.

The Union won the Civil War, simply because it grossly outnumbered the Confederacy, in young men. Grant came to his first position as colonel of an Illinois regiment, acutely aware of this simple fact and charged forward with whatever men he had command of immediately, simply because he knew his losses in combat would always quickly be made up. He was guided by this fact to the end. In 1864, when Hood was pressing Rosecrans at Nashville, Lincoln wired, "No problem, we can get another 60,000 men out of Illinois and Indiana for thirty days services immediately." Instead, he ended up using them to fill Grant's disappearing ranks as he butted heads, quite unsuccessfully, with Lee.

The New York Times

May 1863

Comment

This "style of warfare;" yes this is Lincoln's style, plain and simple, and he's found Grant to execute it. Lincoln wants McClellan to immediately move on the Richmond defenses, he wants Buell to move just as quickly against Bragg, and he wants Rosecrans to move, too. Grant moves, but there was never a time when he lacked for resources, when he had a problem coming up with the most men. He always came up with the most men, there was never a time when Grant found himself in a general battle, without the most men. Lincoln's crowd were running things, relentlessly, remorselessly, from the back end to the throat.

When did General Lee ever have the most men? Was that in the Seven Days? At Chancellorsville, at Second Manassas, at Antietam? The Wilderness? Spotsylvania? Cold Harbor? Or was is at Petersburg and Gettysburg? When the chips are down, which general will you go into the fire for?

Joe Ryan

| Read all Joe Ryan Original Works | Comments and Questions to the Author |

|

Joe Ryan Original Works @ AmericanCivilWar.com Joe Ryan Video Battlewalks |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

About the author: Joe Ryan is a Los Angeles trial lawyer who has traveled the route of the Army of Northern Virginia, from Richmond to Gettysburg, several times. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Battle of Gettysburg

General Robert E. Lee

General JEB Stuart

General Jubal Early

Confederate Commanders

General Joseph Hooker

Union Generals

American Civil War Exhibits

State Battle Maps

Civil War Timeline

Women in the Civil War